Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

Henry M. Miller, HSMC Director of Research

This blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

May 4, 2012

As of this writing, I have exactly one month left in Great Britain, or “Old Blighty” as the World War I British troops called it. Among my activities have been trips to the National Archives at Kew and the British Library. Known for years as the Public Records Office or PRO in London, they changed the name to The National Archives when the new facility was opened at Kew. It is a remarkable place that stores over 11 million documents to which you can gain access. The reading room for special documents is full of people looking at everything from Medieval parchments and letters to the Henry VIII to recently released Cold War records.

Among the documents I have been able to inspect and copy are the wills of Cecil and Charles Calvert, a John Lewgar who might be the father of the builder of St. Johns, Jane Calvert, 2nd wife of Philip Calvert and the likely mother of the little baby we found in the lead coffin at the Chapel, Thomas Cornwalleys, St. Mary’s City designer Jerome White, and a variety of others. But there are also numerous court cases of relevance, petitions from Cecil Calvert and others, tax records and certificates of residence. For example, one shows that in 1663 that Cecil Calvert lived in London and owed 4 £ sterling a year for one tax. He also owed what is known as a Hearth Tax, established in 1662 by Charles II as a way of raising government revenue. What is outstanding about them is that the tax collector listed the individuals by street in London, and this gives us a clear record of Lord Baltimore’s neighbors as well as the number of fireplaces in his house. Just down the street from Cecil Lord Baltimore lived Humphrey Weld and his wife, a sister of Anne Arundell. And at various times, the French and Portuguese ambassadors lived on the street as well. Their residences would have had Catholic chapels where Cecil could have worshiped, although he also had a personal chaplain living with him. One significant find is the inventory of Cecil Calvert’s residences taken shortly after his death in late 1675. I came across this two years ago and was really thrilled to see such a document.

However, in the excitement, I somehow failed to photograph the page listing all the kitchen equipment, so had to return and capture that page.

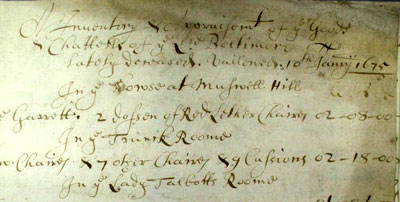

And the surprise is that there is just not one inventory, but two. One is on parchment and appears to be the “field copy” where the items were actually examined and listed. The second one is on fine quality paper and very neatly written. I show you here the heading of this copy.

What is grand about having an inventory is that it gives us a unique perspective on the material world of someone. When coupled with things like the Hearth Tax, correspondence, their will, and other documents, we can gain a far more detailed and sensitive understanding of a person.

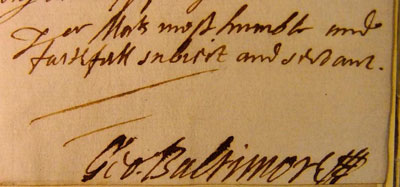

While at Kew, I was also able to examine what represents the true beginning point of Maryland. It is not the Charter issued on 20 June 1632. It really dates back to August of 1629. At that time, George Calvert has just spent a miserable winter in Newfoundland at his Ferryland settlement. While still wishing to colonize and expand his nation’s empire, the cold North was not the place for him. Hence, he penned a heartfelt letter to King Charles I describing the situation and conditions with the oft quoted words “From the midst of October to the midst of May there is a sad face of winter upon all this land.” It is in this poignant letter that he asks the king for a new grant of land in a warmer place, and that place was the Chesapeake. Hence, this document really does represent the beginning of the quest for a new colony that would become Maryland. I felt so incredibly privileged to be holding this precious piece of paper, knowing that both George Calvert and King Charles had also held it. Below is the final section of this letter, with due credit to the National Archives of Britain. It shows George Baltimore’s signature, and he ended it with “Your Majesty’s most Humble and Faithful Subject and Servant.”

In a previous posting, I presented information on the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin that George Calvert worshiped in and where the degrees of B.A. and an honorary M.A. were conferred upon him. This was the place that John Lewgar also received his degrees. But after nearly 400 years, they stopped that practice. The reason was a new structure especially built for University events. It was begun around the same time as the Brick Chapel at St. Mary’s City, but in this case, we know who the architect was who designed it – Sir Christopher Wren. Born in 1632 only a few miles from where Cecil Calvert and Anne Arundell were living at Wardour, Wren attended Wadham College here in Oxford and went on to become a major scientist, astronomer, mathematician, and of course, architect. The then Archbishop of Canterbury Gilbert Sheldon, who was also Chancellor of Oxford University, asked him to design a new venue for the university in 1663. It was the first building Wren constructed.

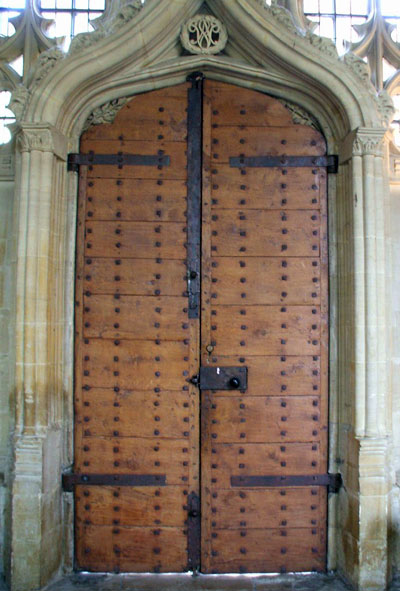

Gilbert Sheldon studied at Trinity College with John Lewgar and Cecil Calvert was certainly an acquaintance. He personally donated nearly 15,000£ for the new building, thus meriting its name – The Sheldonian Theater. Construction occurred between 1663 and 1669; precisely overlapping that of the Brick Chapel. Inspiring Wren were illustrations of the ruins of the Theatre of Marcellus in Rome. The building has a plan in the shape of a “U” with the curved side toward the street and the flat side facing the Divinity School of the Bodleian Library. Wren even cut a door into the Divinity School to allow processions to assemble there and go into his new theatre. Elements of this 1669 doorway, seen below, helped guide the design for our chapel doors at St. Mary’s.

If you look closely, you can see a prominent “W” over the door for Wren.

The street side of the Sheldonian has beautiful stone carving and is the main entrance today. Carved there is a dedication to the reigning king Charles II. This was the first classically inspired building in Oxford, where Gothic tended to prevail. However, classical structures were already being erected elsewhere in England, so it was only revolutionary in Oxford in terms of classical inspiration.

But it was unique as a space for theater. The challenge was it had to be a large, enclosed open space. In Rome, the original would have been open to the sky, but that is not practical in the latitude of Oxford. So Wren came up with a novel roof structure that allowed the area to be successfully spanned. He was so proud of the solution that he presented the plan to the Royal Society in 1663. Here you can see some of massive oak timbers that support the roof of this nearly 350 year old building. While the building does not display the maturity of later Wren buildings, as the famous architecture historian Nicholaus Pevsner puts it, it is an impressive structure that has served the university well.

Inside is a large open space with a gallery. There are many architectural details that are a delight to see. Some are inspired by Roman precedents, as you might expect, and the crest of the University is prominently displayed.

It also has classical columns and paneling inside, imparting an elegant appearance to the structure. Note the columns you see here. They look like marble but are in fact hollow and made of wood, being painted to look like stone. I include a close-up of them for you to more closely inspect. Why these are of note is that the altar in the St. Mary’s chapel almost certainly had columns behind the altar, columns that supported an elaborate pediment and between them was a large piece of religious art. It is highly unlikely that the chapel had imported marble columns either. Thus, the Sheldonian provides an excellent and perfectly dated model to help guide the design of the altar. (Sheldonian marble columns and Sheldonian close-up of column)

The ceiling was painted by order of Charles II and recently restored. The artist was a court painter named Robert Streeter. The subject of the painting is the Triumph of Religion, the Arts and Sciences over Envy, Malice and Hatred. What is somewhat unusual are the yellow colored divisions seen in the painting. These were intentionally added by Wren to simulate the awning or velarium supports that covered the seating area of the Colosseum and Roman theatres to protect the audience.

He was definitely trying to impart as much of the Roman feel as possible. Much more could be said about the many features of this fascinating structure.

I was fortunate to observe a major event in this building. Back in March, a debate in the Sheldonian was held between the Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams and the Archatheist of Britain Richard Dawkins. A University Philosopher was the moderator and the topic was “The Nature of Human Beings and the Question of their Ultimate Origin.” Before the debate began, the moderator asked the two if they could agree on three principles that would guide their responses. These were 1) There is objective truth in this world; 2) Logic is key for finding truth, and 3) Science is an essential process for knowing. They agreed. While this might not seem important, there is a certain fashionable thought today in academia that truth does not exist, all is subjective. So it was notable that both the Archbishop and the famous Oxford Don were in agreement on that. For 1.5 hours, they discussed a range of topics and agreed that the idea Consciousness is an Illusion is nonsense and understanding how and what being a conscious being means is one of the great unanswered questions. All in all, it was a most interesting event. In my opinion, Williams and Dawkins each held their own rather well, with no mortal wounds or knockout arguments delivered.

Religion is all around you here in Oxford with numerous churches, ringing bells, Anglican and Catholic priests, Gray and Black Friars, nuns and Buddist monks regularly seen walking along the city streets. And over virtually every college entry tower are statues of Mary, saints, or a bishop. Here is the entrance to St. John’s College, established in the 1550s.

Today, I went to a special service at 6:00 in the evening at the Oxford Oratory. An Oratory is a group of Catholic priests who voluntarily live together, administer to a parish, but also conduct research, writing, and other activities. Here in England it was started by John Henry Newman, a leader of the Anglican ”Oxford Movement” in the nineteenth century who became a Catholic, made a Cardinal, and may soon be a saint. Anyway, they have annually at the Oratory a special mass on 4 May for the Martyrs of England and Wales. There were several hundred people executed for their faith in the 16th and 17th centuries here and this mass is to remember and honor them. What especially fascinated me is that it was done in the exact form of a sixteenth- or seventeenth-century high mass. All was in Latin, even the epistle and gospel, with only the sermon in English. This was like the experience of George, Cecil , Leonard, Philip and Charles Calvert, John Lewgar, Andrew White, Jerome Hawley, Margaret Brent, Thomas Cornwalli, and many other Maryland founders and they would have instantly recognized it. The fact that on a Friday evening the church was nearly full for this special service was rather surprising, and does demonstrate a desire to remember past events. When I closed my eyes and focused on the fragrance and sound of the music and Latin, it was almost like being in a time machine, imagining being in the Royal Chapel with Henrietta Maria shortly after her husband told her a new colony would be named for her, or with Philip and Charles Calvert at the Chapel of St. Mary’s in the 1670s. One can sometimes feel a connection to them with such experiences that goes beyond intellect into emotion.

On the way back, I stopped at the grocery for a few items and proceeded to walk to the apartment. Along the way, two nicely dressed young men came up and asked me if I needed any help, as I was loaded down. Responding no, I thanked them and we engaged in a brief conversation. They are Mormon missionaries doing their obligatory service for their church. Both had name badges identifying them as members of the Church of Latter Day Saints, and one was “Elder Romney”. Somewhat intrigued, I asked if he was any relation to the Republican nominee for President. “Yes”, he said, “we are cousins”. Now that was a surprise on a street in Oxford!

Something I have been meaning to mention is signs. They have many here that differ quite a bit from ours. Oxford may be the only place that has a thoroughfare named after Logic.

At the library, a sign gives the time it takes to retrieve a document, calling it the “Fetch Time.” And driving is an experience. Not only are you on the left side of the road, and sitting on the right side of the car, but you see many different road signs. Some are clear such as “Kill Speed Now,”, or “Dual Carriageway” for divided highway. But “Slip Road” is a new one, meaning an access or egress lane. “Queues Likely” is easy to understand but what is “Adverse Camber”? We finally determined that means steep hill or incline. When you reach Kew on the London Tube, they tell you to “alight”.

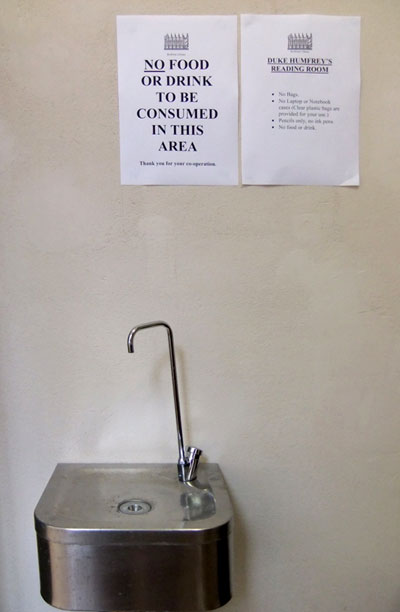

Another is rather baffling. In the Bodleian Library, directly over the water fountain is the sign “No food or Drink to be consumed In This Area”. Go figure.

But one of my favorites is a sign at one of the major archaeological sites, the famous Sutton Hoo burial of an Anglo-Saxon King in his ship with all kinds of amazing artifacts. The sign informs the visitor of a fact that it is hard to dispute at virtually any cemetery.

‘Til next time.