Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

Henry M. Miller, HSMC Director of Research

his blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

May 19

I have been spending a lot of time on buses to London and back, visiting various archives. There are two good services here and round trip costs 13£ ($21). One has a double decker bus and it is fun to get in the very front seat on top.

Since this is such a regular part of the week getting to varied archives, I thought it might be interesting for you to come along for the trip and see some of the sights on the Road to London. When we departure Oxford around 7 AM, we drive down Oxford’s High Street.

The main roads are good and there is lots of interesting scenery. Principal highways (called carriageways and labeled as “M” Roads) are like ours- divided and with multiple lanes – although Brits drive on the left side as you know.

Toward London we pass lovely vistas. Wheat is still an important crop and fields of wheat are interspersed with pasture and other crops.

In later April and May, many fields appear as a vast sea of brilliant canary yellow. This is due to the flowering of the rape plant. Its seeds yield an oil that is in high demand in India and China and English farmers are responding to that demand. The result is even more vibrant and colorful landscape than normal.

One also views lots of pastures with cattle and especially sheep. Note in this picture that the field itself has a series of ridges and hollows. These sheep are grazing on what was 500 or 600 years ago a agriculture field growing wheat and barley using the medieval system called ridge and furrow farming. And this image also shows the ridges running in different directions. Indicating what was once an ancient division of land into furlongs that typified the medieval agrarian method in the Midlands of England.

With enclosure and a shift to grazing that began in the later 1500s, grass covered these former fields, preserving the evidence of earlier land use activities. One advantage of this system is that the lower areas retain water better while the ridges tend to be drier. Thus, no matter if it is a wet or dry summer, there is a good chance that at least some of the grain will mature for harvest. A bit later in the month, this same field shows color variation indicative of this differential moisture and plant growth., with the ridges yellow and furrows more green.

Not 1000 feet further long, just past a hedge row, the land has been more recently plowed and all surface trace of this medieval farming practice is now obliterated.

Modern agriculture with deep plowing using powerful equipment is unfortunately quite destructive to ancient evidence like this, so it is only areas that have continually served as pastureland for centuries where this information survives to be observed. This is a serious concern for archaeologists as traces of Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Age, Roman and Saxon earthworks and land usage, as well as entire abandoned Medieval villages can be almost totally erased with a few plowings.

A short distance away on the same side of the road, you catch a glimpse of a village with its ancient church and other buildings, perhaps this is where these Medieval people who created and farmed these very fields once lived

We also go past more recent facilities such as an airport. The first few times, it looked interesting but there was no sign identifying it, so I just assumed it was a small County airfield.

But my assumptions about this place were totally wrong. The first clue should have been buildings suggesting it had some historical depth. These are World War II era Nissen or Quonset Huts as they were called in the U.S of A.– half circular metal structures that were manufactured in large quantities and could be rapidly erected for purposes ranging from troop barracks and dining halls to aircraft hangers.

The reason for their presence was answered in a conversation with archivist Peter Kemp . It is the RAF Northolt base, one of the earliest airfields in England, established in 1915. In the Second World War, it became a vital element in the Battle of Britain. From this field flew Hurricane fighters piloted by British and Polish airmen to combat the massive aerial assault of Hitler’s airforce. The Polish Squadron based here scored the highest number of enemy aircraft “kills” of any group in the battle, and of the 30 pilots from this base killed during that long fight, one third were Poles. This explains the sign along the highway you see here.

Although the Luftwaffe aggressively bombed RAF facilities all over England during this famous battle, they had little effect on Northolt. Indeed, of the 4000 bombs that were dropped to destroy this facility, only two actually hit the airdrome. Were German bombardiers really that bad a shot? No. It seems the base commander looked at the airfield that was surrounded by housing and decided that a big piece of open land here would make the field rather obvious to the Luftwaffe. So he had the field camouflaged as housing, complete with the hangers looking like houses with gardens and a fake stream and roads crossing the runway. This reportedly worked so well that even British pilots newly assigned to Northolt had trouble finding the field the first time.

It is from Northolt that Winston Churchill flew to his varied meetings with British Commanders in North Africa, bolstering flagging British moral in the fight against the talented Desert Fox, General Rommel. Recently a direct link to that fight has been discovered in North Africa. It is a P-40 fighter found incredibly well preserved in the Libyan desert over 100 miles from the coast.

It tells a tragic and unknown 70 year old story that is hard to forget. It is the story of a 24 year old British pilot who in June of 1942 got lost, had to land in the desert and after trying to use his radio to summon help, walked to his death in the unforgiving sands of Libya. His struggle with thirst, heat, cold, desperation, and loneliness haunts me. Just as the dryness of the desert has preserved Egyptian mummies and other artifacts, the aircraft is in amazing shape with the instrument panel still readable, the machine guns and ammunition intact, and the parachute still laying beside the plane, which the pilot apparently used for shelter. And somewhere out in that vast expanse of sand lies the mummy of 24 year old airman Dennis Copping, a long forgotten victim of World War II. I wonder if Copping ever flew from Northolt?

RAF Northolt is also the place Churchill used to fly to meetings with President Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin. Immediately after the war, this facility served as the main airport for London until Heathrow could be built. And there is a sad more recent event associated with Northolt. It is where the body of Princess Diana was returned to England after her fatal car crash in Paris.

As we move closer to London, traffic becomes more congested, the same as in U.S. cities. One major problem is that there is only one main road between Oxford and London. And when accidents occur on this highway, travel becomes a mess.

During the many trips, the fastest time between these two places by bus was one hour and 25 minutes. What do you guess might be the longest? Three hours? Four? No, the longest was a true endurance test. We left Oxford at 7:00 and arrived at Victoria Station at 1:20 in the afternoon – over 6 hours. The bus driver was totally exhausted, as he had to navigate backroads in heavy traffic most of the way to London. Thankfully, there was a toilet on the bus. The only positive was the opportunity to see small towns, countryside and houses I would never have otherwise been past. Here are a few scenes from that “experience.” Note the creative use of brickwork noggin on the house with the lovely flowers.

During the many trips, the fastest time between these two places by bus was one hour and 25 minutes. What do you guess might be the longest? Three hours? Four? No, the longest was a true endurance test. We left Oxford at 7:00 and arrived at Victoria Station at 1:20 in the afternoon – over 6 hours. The bus driver was totally exhausted, as he had to navigate backroads in heavy traffic most of the way to London. Thankfully, there was a toilet on the bus. The only positive was the opportunity to see small towns, countryside and houses I would never have otherwise been past. Here are a few scenes from that “experience.” Note the creative use of brickwork noggin on the house with the lovely flowers.

One of my destinations has been the British Museum. It has millions of volumes and is the largest library in England. Holdings range from 700 A. D psalm books, Medieval manuscripts and one of the original copies of the Magna Carta to Shakespeare’s First Folio and the writing desk of Jane Austin. My goal, however, are the manuscripts.

They own half a dozen letters from Cecil Calvert that I have now transcribed. The one real pain with the British Library is that they do not allow you to take photos of the documents. Hence, the only approved ways of gaining the information is to transcribe the document using either a sharp pencil or a laptop. There is a wonderfully preserved wax seal from Lord Baltimore on one of these letters that I would love to have an image of but they charge £25 (about $39) which is rather steep for a picture.

Another item is a copy of a letter written by William Chillingworth to John Lewgar while Lewgar was living at St. Mary’s City. They were fellow students at Trinity College and friends. Chillingworth converted from the Church of England to the Catholic Church around the same time Lewgar made that change. Chillingworth’s was a big deal because his godfather was the Archbishop of Canterbury. But after a year in a Jesuit school in Flanders, Chillingworth returned to the Anglican fold and he and Lewgar exchanged in a series of letters about this. It seems that little has survived of these exchanges at the British Library, aside from this letter, but one of Lewgar’s responses was published in the 1680s.

Still another item is the letterbook of Philip Stanhope, Lord Chesterfield. A friend of Maryland’s Surveyor General Jerome White, my hope was that some mention or even a letter from or about Jerome would be in this book. Alas, that is not the case. But it did reveal that Stanhope was apparently a Romeo and wrote a long series of love letters to women, and some of these letters are so exquisite that they very likely melted some reluctant hearts. To my surprise, one of his correspondents was “Mrs. Calvert borne in Maryland and a Romanist”. Based upon the evidence, this is almost certainly the mother of the little baby we found in the lead coffin at the Chapel – Jane Sewall Calvert. She was the second wife of Philip Calvert and came to England with her mother and step-father, Charles Calvert, in the mid-1680s. The letters seem to date to the 1685-1690 period, when Jane would have been between 18 and 23 years old. He concludes the letter “til I have the happiness of seeing you a gain in our Dear Square (as you call it), which is often though on with pleasure and your absence with trouble” . “Our Dear Square” is probably what was then called Southampton Square in Bloomsbury in London, the place Charles Lord Baltimore lived. Was Lord Chesterfield hitting on the young and perhaps naïve but quite wealthy widow from the colonies? Or was this an innocent relationship of a well know courtier assisting a young woman new in town? Transcribing a second letter to her next week might provide more clues.

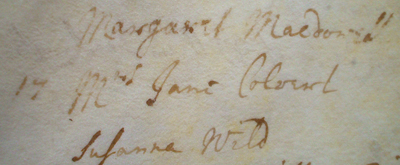

Regrettably, Jane did not live long afterward, for in the burial register of St. Giles in the Fields, there is a listing for a Mrs. Jane Calvert interred there on 17 May 1692, as you can see below. She did leave a will and I now have a copy of that in hand, waiting to be transcribed.

This coming week I hope to finally gain access to the Old Brotherhood Archives at Westminster. Permission is required and the proper authority has been contacted. These are the records of the “Secular” priests in England in the seventeenth century, meaning those that were not member of an order like the Jesuits or Dominicans. No telling what they might contain but there is a suggestion that Cecil Calvert’s chaplain in the last decade of his life was a Humphrey Waring, the Dean of the Chapter of these secular priests. So here is hoping for some more valuable evidence.