Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

This blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

November 27, 2011

I hope all had a pleasant Thanksgiving with family and friends. This is not a day observed here in England, so Thursday the 24th is just another work day. However, the American students at CRMS did host a special dinner to which I was invited. On Saturday the 19th, they prepared a fine feast including turkey at St. Michael’s Hall. We had a most enjoyable time.

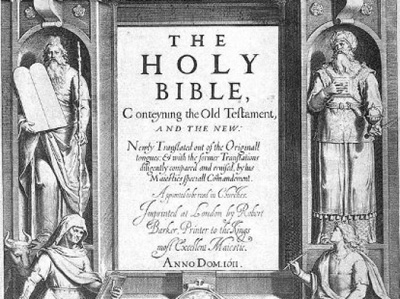

There was a special event held in London a little over a week ago that caught my attention because the Queen attended. It was the concluding episode in the year-long celebration of the 400thanniversary of the King James Bible, first printed in 1611. Original copies of this famous work were brought out for rare display.

In 1610, the standard bible for clergy and the more educated members of society was still the Latin Vulgate, in use since St. Jerome created it from Greek and Hebrew texts around 400 A. D. This version had shaped Christianity for over a thousand years. The first English translation was made by William Tyndale during the reign of Henry the 8th and, following some revisions, it became known as The Great Bible. After the Catholic Queen Mary took the English throne in 1553, some Protestants became refugees and went to Geneva, where they produced a translation more in line with Calvinist ideas. This Geneva Bible was published in 1560 and used in Britain, especially Scotland. But both had flaws and did not well conform to the needs of the Church of England as it was evolving. When Scottish King James the 6th took the English crown in 1603, becoming James 1, one of his first actions was to order a new English bible. Work by 47 scholars at Cambridge, Oxford and Westminster commenced in 1604 and continued for seven years, resulting in a work that came to be the center of Anglican worship. It was published in 1611 and an image of that first page is seen here.

During Maryland’s early decades, this version gradually came into wide use by the English church, especially after 1660 when it was fully incorporated into the Book of Common Prayer.

What about the English Catholics? It is unlikely they used the King James Bible, and research suggests that the Latin Vulgate remained the standard work for Catholic worship. However, the need for an English translation was still recognized in part to compete with Protestant versions. This task was taken up by a group of Oxford University refugees who went to Douai in France. They established the English College there in the mid 1500s, a school that was later attended by a number of Maryland colonists including Father Andrew White. In the late 1570s, these former Oxford scholars began translating the New Testament into English and published it in 1582. Their work on the Old Testament proceeded and was finished in the early 17th century. Known as the Douay-Rheims Bible because the first printing occurred in the city of Rheims, it became the standard English bible of Catholics for the next 350 years and is still in use, although with revisions. It is also known as the Rhenish Bible and his probate inventory tells us that Philip Calvert used a copy of this Catholic bible at his home in St. Mary’s City. The Douay-Rheims translation influenced the scholars working on the new version for King James and also introduced a number of new words from Latin into the English language, such as accusation, allegory, character, cooperate, victim, and appropriately for this season of the year – advent.

But it is the King James version that had the larger impact. Designed to be read aloud, its creators gave it a beauty and poetry that are magnificent. From common expressions to Christmas songs, its verses are still widely used even today. Unfortunately, recent biblical translators tend to lose its graceful poetry, reflecting a less eloquent and more stark utilitarian age. For example, “a babe wrapped in swaddling clothes” becomes “a baby wrapped up in stripes of cloth”, or “make a joyful noise unto the Lord” morphs into “Acclaim Yahweh” and a “A coat of many colors” is rendered “a decorated tunic.” I leave you with one final example, pointed out by Dr. Peter Mullen, the rector of St. Michael at Cornhill, London. He describes one of his favorite psalms (139) that in the King James Bible relates that God knew the writer “while he was yet in his mother’s womb – thine eyes did see my substance, yet being unperfect.” The New Jerusalem Bible presents this as “Your eyes could see my embryo.”

King James’s bible conveys the style of William Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser, and John Donne, a style characteristic of the era during which George Calvert grew up and became an adult. This bible’s memorable passages were read and used by George Calvert and many Marylanders through the 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. And its phrases are still a part of contemporary language. Have you ever heard “the powers that be”, “the apple of his eye,” the writing on the wall”, “through a glass darkly” or “wolves in sheep’s clothing?” All come from this work. My bet is that old King James never imagined the enduring impact his commission for a new bible would have.

A portion of my efforts here have been focused on the nature of the Oxford education of Maryland’s founders. From examining the careers of the Governor’s Council and other persons in Maryland during the 17th century, it has become clear that those with college education went to one of two places – Oxford in England, or Catholic schools on the continent in either Flanders, France, Portugal, and/or Italy. Unlike Virginia, few Maryland settlers seem to have attended Cambridge. Not only did George and Cecil Calvert and John Lewger study at Oxford, but the first Anglican minister in Maryland, William Wilkinson, studied there, as did that notorious rebel, John Coode. And the first Royal Governor, Sir Lionel Copley, was an Oxford graduate. So this place undeniably helped form the perspectives of a number of individuals who played important roles in Maryland. Understanding the nature of the curriculum they studied, whether at Oxford or in the Continental schools, is essential. What subjects did everyone study as required by University and college statutes? And what were the more specialized topics they would have investigated with tutors? How different was the Oxford curriculum compared to that in Belgium or France? Answering such questions is vital for understanding the intellectual backgrounds that helped shape Maryland.

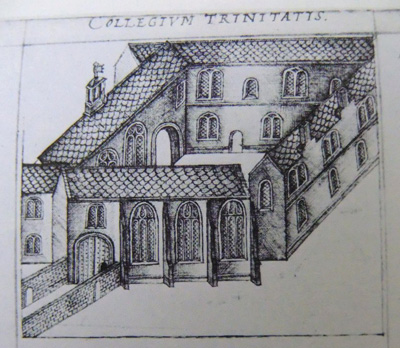

The educational institution that perhaps had the greatest influence was Trinity College at Oxford, where George Calvert received his B. A., Cecil Calvert spent several years studying, and John Lewger obtained both a B. A. and a M.A.. Trinity College was founded in 1555 by a Catholic, Sir Thomas Pope, during the brief reign of Queen Mary. He was given a complex of abandoned buildings that had been Durham College, a medieval school for monks from the city of Durham in Yorkshire. Henry the 8th closed the school as part of his Dissolution of the Monasteries in Reformation. Trinity got off to a good start but with the death of Mary and crowning of Elizabeth, it had to make a shift to Protestantism to survive. This was gradually done, but it seems that Trinity retained “popish” aspects at least into the mid-1580s, and perhaps longer. With a solid educational program, the college thrived and it became one of the institutions attended by the elite of English society.

This picture drawn in 1566 is the oldest surviving of Trinity and shows the college as it would have appeared when George Calvert studied there.

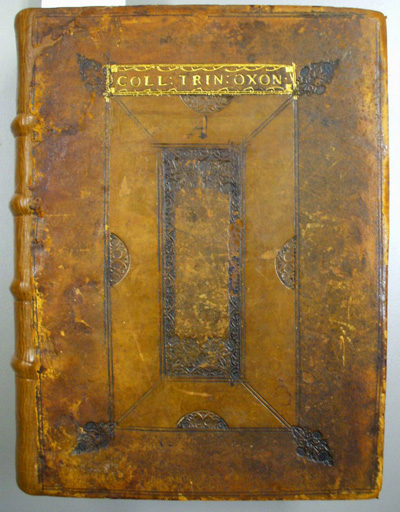

You can see the buildings arranged around a quadrangle that still exists. The structure in the foreground is the Chapel while the one on the right is the library and the hall is on the left. British Prime Ministers, diplomats, Archbishops of Canterbury, and other prominent individuals are among its alumni. As one historian has written about 16th-century Trinity College, “The most distinguished Trinity commoner of his time was certainly George Calvert.” Calvert came to Trinity when he was about 14 years old, in 1594 and graduated in 1598. Cecil Calvert studied at Trinity between 1620 and 1622, while John Lewger matriculated at Trinity in 1613, was granted a B. A. in 1619 and a M. A. in 1622. A decade later, after being ordained in the Church of England, he was awarded a Bachelor of Divinity degree. Understanding what they did at this college involves examining the college histories, statutes that defined the overall educational programs, and exploring the college archives. In this I have been greatly assisted by archivist Clare Hopkins. She gave access to the original documents, as well as providing much insight based upon her research. In 2005, Clare published Trinity College: 450 Years of an Oxford College Community and it has proven most helpful. Among the many holdings of the college is the original 1556 strong chest in which money, the charter, account books and other documents were secured. As this picture shows, it had three locks, the keys of which were possessed by three different persons to insure no unauthorized access.

It is in remarkable condition, despite the successful efforts of Cromwellian looters to open it. Regrettably, many of the original documents were destroyed during the siege of Oxford in the 1640s, when the city served as England’s capital under King Charles 1. But a college bursar wisely took a number of the books with him when he went into “the country” to escape the plundering, and these books have survived. The most significant of these is a large volume that holds documents of the 16th and 17th centuries.

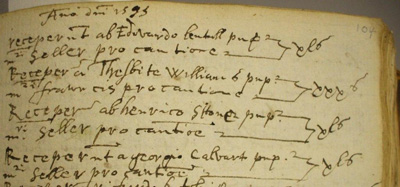

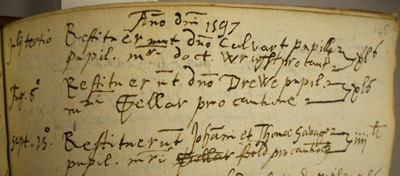

The earliest evidence of George Calvert at Trinity is found on a list in this book that records “caution money,” a fee each student was to pay to cover any damage or other expenses they may incur. The earliest year for which caution money lists survive is 1595 and there, the fourth student recorded on the list, is George Calvert.

This document tells us that he was a student of Master Sellers, his tutor, and paid 40 shillings. As Clare notes, the rate varied between 30 shillings for the poorest students and 80 shilling for the elite, placing George at the lower end of the scale. When he matriculated, the University register lists him as a plebeian, or commoner, so this fee level matches that status. In the 1597 Caution money account, George is the first student listed in July, and was then a student of Mr. Doct Wright.

These give us vital clues, because they tell us who the men were who supervised George’s education during his years at Trinity. Since the mid-16th century, tutors had become central in the educational program of Oxford. A tutor would guide the student’s studies, lecture them, assess their performance, provide books and financial oversight, and in general serve as the stand-in for parents. Master Teller is described as a Lecturer in Philosophy and little else is currently known about him. In contrast, Mr. Doctor Wright is Robert Wright. He was an accomplished scholar who later became an Anglican Bishop. There is good evidence that Wright and George Calvert remained close. As Secretary of State, George wrote letters of support for Wright to be appointed a bishop. And when Wright’s son was born in 1621, he was named Calvert Wright. But when George converted to Catholicism, this must have had a major impact upon their relationship; this subject is still being explored.

There is little left architecturally of Trinity from the time George Calvert was a student. One building that does remain is the library, part of the original late15th and 16th century Durham college.

Located on the second floor of this structure, undergraduates were not permitted to use the library during in the late 16th and 17th century, and an undergraduate library was not established until 1683. Hence, it is unlikely that George was in this space. Later, as a Fellow, John Lewger would have spent considerable time in there. While George was not in this space, the library does contain some items that he, his son Cecil, and John Lewger would immediately recognized. These are stained glass windows. The windows were originally in the 16th-century church of the college, which was demolished in the early 1690s. Fortunately, someone thought to save the stained glass. Later, these were repaired and installed in the library. One represents the image of St. Augustine.

St. Swithun was an Anglo Saxon Bishop of Winchester, who died around 860. He became another popular English aaint and his presence shows continuity between Anglo Saxon, Norman and Tudor worship. His tomb was also destroyed by Henry VIII as part of the Reformation.

St. Swithun’s feast day is 15 July and there is a still heard a bit of ancient lore attached to him. The verse goes:

For Forty days it will remain

St. Swithun’s day if thou be fair

For forty days ’twill rain nae mare

So beware of rain in mid-July. It seems clear that St. Swithun also remained popular at Trinity College in the 16th century”.

Another window bears the likeness of St. Thomas of Canterbury, also known as Thomas Beckett, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was assassinated in 1170 within his Cathedral.

Thomas Becket became a widely venerated English saint for both Catholics and Anglicans. The place he was executed by four knights was always remembered and is marked today, as this picture shows, with four daggers.

The survival of these windows is rather remarkable, especially that of Becket. King Henry VIII ordered the destruction of the Becket funerary monument at Canterbury Cathedral, as part of his Reformation, and its former location is marked today as can be seen by this plaque

A candle is kept burning where the tomb once stood. This was a place of great importance to English people who came to it on pilgrimages in the Medieval era. As you may remember, Chaucer set his tale with pilgrims heading to Canterbury to pray at St. Thomas Becket’s tomb.

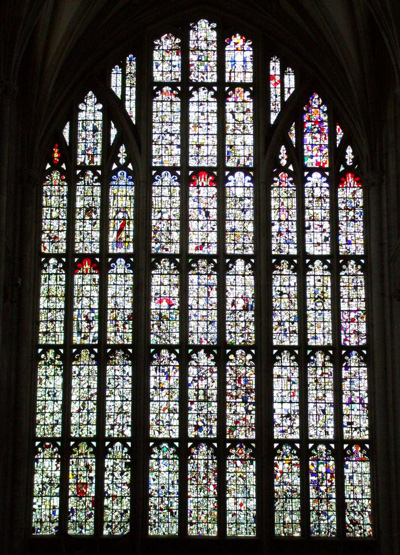

Given the negative political view of Becket that emerged during the Reformation, it is amazing that this Trinity window survived. How this happened is uncertain. But we do know that the students at Trinity would have seen these windows. They were expected to attended daily worship services at Trinity, so George Calvert, as well as John Lewger and Cecil Calvert would have likewise viewed these specimens of religious art on a regular basis. The Trinity librarian tells me that these were probably part of the earlier Durham College Chapel, and thus are among the older stained glass to survive in Oxford. Due to hostility to “popish” images, there was great destruction of artwork and windows by zealous reformers in the 16th century and as well as by parliamentary forces in the 17th century. The story of this destruction of so much of medieval religious art is brilliantly captured in Eamon Duffy’s memorable book The Stripping of the Altars. Visible evidence of this can be seen in defaced carving as well as a fascinating feature of many cathedrals. Throughout England, huge spans of beautiful stained glass with religious themes were broken out and the sections smashed. In some cases, parishioners saved the glass pieces and these were remounted during the Restoration or in later times. Due to the breakage, however, it proved impossible to reconstruct the original images. Instead, you see windows with random patterns of colored glass, reflecting the fragmented nature of what were once beautiful specimens of sacred art. The immense western window of Winchester Cathedral, seen in this view of the church, was completely broken out.

A man picked up the many pieces, hid them, and they were later used to restore the window in an arbitrary pattern of glass fragments as seen here.

We also see this at other places like Wells Cathedral, where some of the brilliantly colored fragments were later mounted in a horizontal arrangement.

How the stained glass windows at Trinity survived such wanton destruction is a true mystery. But they give us one of the few direct links to the Christian imagery that the Calverts and Lewger would have seen with their own eyes. This was part of their experience. Thus, it is essential to recognize that, while college life today is completely secular in most institutions, the University experiences of Maryland’s founders were not secular but fully integrated with and immersed in faith. It involved daily religious readings during meals, participation in services and regular sermons. When we contemplate The Maryland Design and the place of religion and conscience in Lord Baltimore’s policy, this background cannot be ignored.

I’ll write more on Trinity College and the experiences of the Calverts and Lewger there in a future posting.