Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

Henry M. Miller, HSMC Director of Research

This blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

April 12, 2012

Work continues at a fast pace here as time is beginning to run short. One of my goals was to return to a small village church just north of London that has much significance for Maryland. It is only a few miles from the grand mansion built by George Calvert’s patron, Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, called Hatfield House.

Cecil built this in the early 1600s and there is no doubt that George Calvert was familiar with what is one of the grand homes from Jacobean England. It is even possible that he took a few architectural hints from Hatfield when designing his own Kiplin Hall. Incidentally, the Cecil line who gave George his start has never ceased playing a major role in English politics. The current Marquee of Salisbury (14th in the line and who continues to reside at Hatfield), is overseeing the Thames Diamond Jubilee Pageant for Queen Elizabeth. It will be a seven mile long, thousand vessel strong maritime parade through London. Occurring on June 3, the highlight will be the Queen’s new 88 feet long, elaborately gilded barge named Glorianna. Powered by 18 oarsmen, her voyage will be a scene reminiscent of movies, such as in A Man for All Seasons, but for real.

But the place I was determined to visit is the little village of Hertingfordbury. What an unusual combination of suffixes for a place name but the combination goes back to at least 1500. It was the home of the Mynne family and one daughter, Anne, married a young Yorkshire man named George Calvert. Anne became the mother of Cecil, Leonard and the rest of the Calvert family. Over 18 years of marriage, Anne and George had 10 children. But giving birth to an eleventh child, a son named John, both Anne and the baby died in 1622. They were buried at their parish church of St. Martins in the Fields in London. However, George wished to provide a suitable interment and permanent marker for his beloved Anne and he ordered an elegant tomb to be installed at her family burial place. It is this memorial that we were seeking.

With the help of my wife, and a GPS, we rented a car and drove to Hertingfordbury. Finally there was time to properly document the monument. While I have made three prior visits, leading the tours never provides more than a few moments to contemplate the tomb and take a few pictures. Anne is in her ancestral church called St. Mary’s.

Built of cut stone and flint cobbles, an architectural tradition found in this region, it is a 15th-century church although heavily “renovated” by the Victorians. This image gives you a close-up of the spalled flint cobbles that form the walls of the church with one dressed stone corner.

Inside, under the tower, is the Anne Mynne tomb. It is an elegant and beautifully produced sepulchral monument called an Altar Tomb. George Calvert certainly had a major hand in its design and composed the text that is displayed on it.

The inscription is in Latin but with the help of Linda Hall at St. Mary’s College and Nicholas Crowe of CMRS, a good translation is now available. In it, George describes Anne as “a woman born for all outstanding things, and returned to better things, incomparable in piety, modesty, prudence.” Anne is depicted with a full body carving showing her lying peacefully on her back, her head upon a pillow and her hands gently resting at her sides. She wears a dress with brocaded sleeves and her hair is hidden under a cloth cap. All evidence indicates that Anne and George were happily married and he relied upon her. With the weighty responsibilities as a principal Secretary of State for the country, Anne and the family provided essential emotional support. George grieved deeply over the loss of Anne and said on the inscription “Her husband mindful of so sweet a wedded life, overcome by so great a pain and grief and longing, has placed with his hands this monument to his wife for himself, his children, and their posterity.” That posterity includes the many descendants of the Calvert family but also, in a sense, the citizens of Maryland.

One of the most significant things about this tomb is the heraldic symbols depicted on it. One is the Black and Gold of the Calverts. The other is the Red and White of the Mynnes. These are combined in a cartouche at the center of the panel over her figure.

A close inspection will show that the Mynne crest contains a cross form known as the cross botany, also found on Maryland’s flag. This is the first place where the yellow and gold and white and red of Maryland’s flag are seen combined, and linked with the cross botany. Traditionally, the flag has been explained as a combination of the crests of George Calvert’s father and mother, the Calverts and Crosslands. That might be so. However, State Archivist Dr. Edward Papenfuse has suggested that the Mynne crest was perhaps the key inspiration. I have also wondered about that and find his hypothesis compelling. If we go look at the one surviving Mynne tombstone elsewhere in the church (that of her likely brother George Mynne), we see that, although it is mostly hidden under a pew, the cross botany symbols are prominently displayed.

Could this be the original inspiration for the Maryland flag?

This is an impressive although not extravagant tomb compared to some of the others of the period. I am trying to complete its study with the new data now in hand. The visit allowed measurements to finally be taken, and if the carving is at all accurate, Anne was about five feet tall. It is almost certain that she lies encased within a lead coffin in this tomb, as she had to be moved from London to Hertingfordbury months after her death. What did she look like? There are no paintings of her that we currently know about, although it seems possible that the artist worked from a painting or miniature. So the only known image is that of the stone face on her tomb. Previous pictures have all been taken at an angle but Carol and I managed to get up high and finally obtain good images looking directly at Anne. You are the first to see the full face of the mother of Maryland’s founders, Cecil and Leonard Calvert. The damage to her nose is reportedly due to Puritan soldiers during the English Civil War. Perhaps with digital technology, we can repair this damage and create a finer image of this woman who was so important for Maryland’s history.

The next task is to fully study this unique monument, identify and describe its materials and features, and try to discover who the talented artist was that created such a loving memorial.

Nearly all of my time is spent in the Bodleian Library, which is filled with amazing resources, but it is becoming urgent to get to various archives to further pursue data about early Maryland. Still, Oxford remains a fascinating place. Recently HSMC’s Executive Director and her husband visited here and we toured some of the more notable places. And Delaware historical archaeologist Craig Lukezic came to Oxford with his wife Francis, who is working on her master’s degree in archaeological conservation at Cardiff University. One of the places we visited is Merton College. Founded in 1264 by England’s Chancellor Walter de Merton, it is an impressive institution with about 700 fellows, undergraduate and graduate students. And how many institutions in the world could honestly have a sign like this?

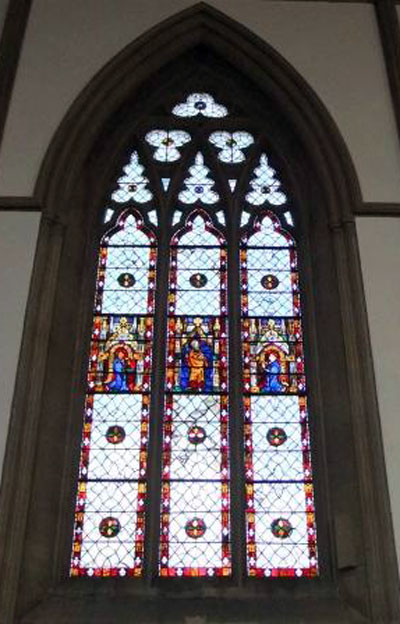

The Merton Chapel begun in 1290 established the prototype for Oxford College chapels. A chancel/choir, central tower crossing with transepts, and, as planned, a long nave. But funds were insufficient and only the altar end, tower and two transepts were built. If completed, it would have been over 200 feet long. But what was built is still impressive.

The east end has a beautifully preserved huge window which is typical, according to the architectural historians, for the period ca. 1300. It is a fine example of the geometric complexity and gracefulness that medieval builders incorporated in constructing these inspiring buildings.

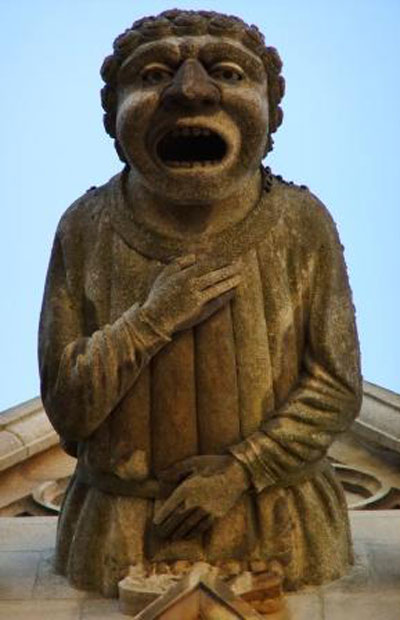

The lead roof is drained through carved stone water spouts. Often these spouts are in the form of strange gargoyles, but the Merton ones tend to be more human in form, such as this poor monk who is doomed to have water spewing from his mouth with every rain.

The inside is lofty with impressive columns but Victorian repairing had left its mark. On the other hand, the windows retain much of their medieval glass, although restored in the 1930s. You can see here that the colored glass was used carefully but very effectively and allowed more light than one might have expected.

The floor of the transepts and tower area is a confusion of stone tomb markers and regular paving stones of ancient date. Some of the markers are no longer legible due to foot wear. And a few older stones have depressed areas that once held brass makers. One is of special interest. (

It shows a man, almost certainly a priest, holding a chalice with a consecrated host in the center. But the bottom part of the marker is missing. Why? This is very probably another piece of evidence of the Reformation. Markers that asked the viewer to pray for the deceased were considered “Popish” and often either removed or obliterated by the Reformers. This appears to be good evidence of such activity in the 1500s.

One very unusual item in the church is made of wood. It is a coffin carrying device for funerals and dates to the seventeenth century.

These allowed a heavy coffin to be more readily carried and the pall cloth could hang properly during the service by having the coffin elevated. Such items rarely survive so this is a notable example of medieval into early modern utilitarian church furniture.

Merton College also has an important feature called the Mob Quadrangle. A square space surrounded by buildings, it dates to the late 1200s and early 1300s and is the oldest quadrangle in Oxford. Such an idea was soon adopted by other schools and you see them today on colleges and universities around the world. Even St. Mary’s College has some quads, inspired by the place you see here.

During the English Civil War, Merton College housed Maryland’s namesake, Queen Henrietta Maria. One wonders if Cecil and Leonard Calvert, who were also reportedly in Oxford at one point in the war, called upon her here? A new discovery (as of 16 April) tells us that they would have known someone at Merton who could have readily facilitated such an audience. And he was also someone who possessed direct knowledge Maryland at the Beginning. The man was Richard Gerard, a commander of the Queen’s Guard who were garrisoned with her at Merton College. Her guard was one of the earliest British military units to be outfitted in red coats and Richard commanded the Queen’s Horse regiment. But how did he know about Maryland? Richard Gerard was one of the 20 gentlemen who sailed on The Ark and Dove in 1633. After a year of so in Maryland, he returned to England, perhaps not relishing frontier life. Shortly afterward, one of his relatives, Thomas Gerard did make the move to Maryland, acquired St. Clements manor, and becoming a notable figure in the colony. After the war, Richard went to the Continent and continued working for the Queen. At the Restoration, he was made a cupbearer to Henrietta Maria.

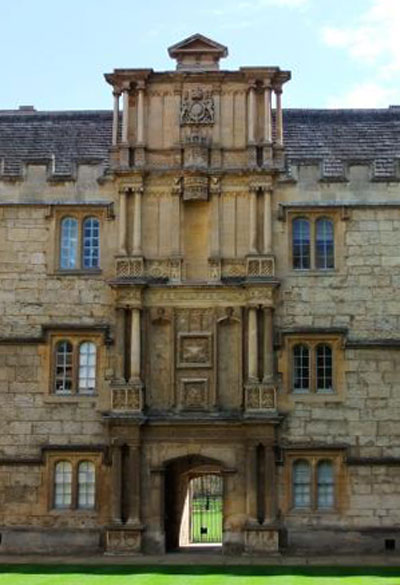

The Queen and Richard Gerard would have no doubt been familiar with most parts of the college, including an area called the Fellow’s Quadrangle. It is also a grassy square but features at the south end a tower similar to that at the Bodleain, although less tall.

Construction started on this in 1608, the same year that Captain John Smith was exploring the Chesapeake Bay for the first time, collecting the information for his famous map. Here in Oxford, stonemasons were busy erecting the walls and creating numerous carved decorative elements on the tower such as the interesting figures you see here.

They are strange creatures that passersby tend to notice. And adjacent to them is a lion with equally intriguing flourishes.

This raises an intriguing question. Almost daily over a period of decades, someone walked past these figures and was intimately familiar with the fanciful stone images found all over Merton. His name was J.R.R. Tolkien and the office where he did a good portion of his writing was in a room next to this tower, looking out over the Christ Church Meadow. One wonders if he gained any ideas from the splendid medieval and seventeenth century artwork that surrounded him in composing works such as Lord of the Rings? Another literary giant you will know of who was at Merton College is T. S. Eliot. So this is a fascinating place that really does have 750 years of heritage behind it.

Spring is here and Oxford has surprises. Walking south toward the Thames from Merton, one goes along Christ Church Meadow, a tract owned by that college for centuries. Although only a few hundred feet from college buildings, the Meadow is still used as pasture for cattle, as you can see here. The nearby tower in the background is Merton Chapel.

In walking along side the meadow, we met up with some unexpected visitors – wild pheasants. This pair was enjoying the spring weather less than 100 feet from a heavily used walkway. While I have occasionally caught glimpses of them in rural areas, finding them in what is almost downtown Oxford was a total surprise.

Finally, spring brings out boaters on the Thames. The legendary Cambridge-Oxford boat race was just held last week. Cambridge was victorious this year and Oxford was not happy. It is along this stretch of the river that the Oxford team starts their training sessions, and you can see someone honing their rowing skills here already. With the colorful geese, ducks and swans, flowing water and puffy white clouds, this is a most tranquil setting only a ten minute walk from Oxford’s traffic clogged High Street, which is what they call Main Street over here.