Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

Henry M. Miller, HSMC Director of Research

This blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

March 11, 2012

I am back in Oxford after a sad and unexpected trip back to the US for the funeral of my sister. It is taking a bit of effort to again become focused.

The last dispatch spoke about the Bodleian Library. Although we think of college libraries as open to all students, and even the public, such was not the case in the 16th or 17th-centuries. Access to the Bodleian repository was restricted to Oxford Ph.D.s and M.A.s. For an undergraduate or outsider to gain admission, they had to apply to the Convocation of the University for special permission, and this was typically granted to only 20 to 30 people each year. Most were scholars from Cambridge, Scotland or European Universities in places like Leiden, Amsterdam, Nuremburg, Saxony or Sweden. A few undergraduates from Oxford colleges were occasionally admitted. Thus it was surprising to discover that one Cecil Calvert received this privilege on 25 June 1621. Other elite students admitted that year were the future Scottish Marquis of Hamilton and sons of the Countesses of Devon and Exeter. Admission was not automatically granted and a solid need to use the library resources had to be demonstrated. While we cannot now determine Cecil’s purpose, the fact that he went to this effort when few other elite students did so at the time suggests a previously undocumented level of curiosity and academic desire in the future founder of Maryland.

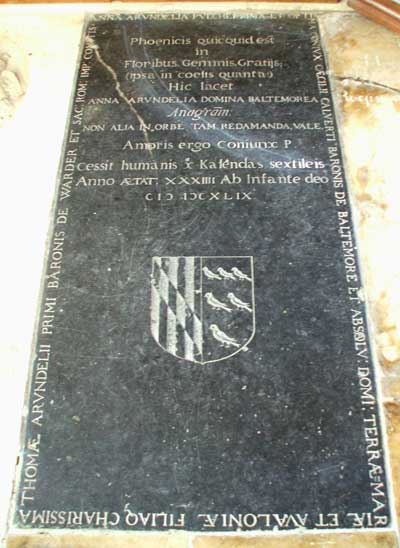

The depth of his education is also indicated by an unusual source, the tombstone verses he composed for his beautiful wife Anne Arundell. She died on 23 July in 1649 and was interred at the traditional Arundell burial site within the church at Tisbury, Wiltshire.

It is not far from Hook House, the home that Cecil and Anne shared. One translation of the central text is

Epitome of all the qualities of the Phoenix

That there are in flowers, buds and graces

(these being as great as there are in Heaven)

Here Lies

Anne Arundell Lady Baltimore

Anagram

Farewell. No other Woman’s love in the world was to be so requited

She left this world on July 23rd in the 1649th Year

From the Childhood of God and 34 years of age

This memorial was set up by her husband for his love’s sake.

Around the border of the large stone is found the following wording:

“Anne Arundell, best and most lovely wife of Cecil Calvert, Baron Baltimore, Lord Absolute of Mary-Land and Avalon, and daughter of the most excellent Thomas Arundell, first Baron Wardor [sic] and Count of the Holy Roman Empire.”

What Barry Williamson and Dr. Nicholas Crowe find especially noteworthy is the highly unusual spelling of the word July. Cecil wrote it as “sextileis,” the sixth month in the old Roman year. But the typical word for this month from about 4 A.D. through the 17th century was “Augustas”. During the later Roman Republic between 100 B. C. and 4 A. D., Romans did spelled it “sextilis” but Cecil’s word is “sextileis”, a more archaic form only found on inscriptions and writings from the early Republic dating before ca. 100 B. C. Why would he have done this? Barry and Nicholas both suggest and I concur that employing a word from the Roman Republic would have been highly appropriate in 1649 England, given that the king had been beheaded in January and a new English “Republic” was being formed to govern the country. This may have been a deliberate use of the ancient form to display republican sympathy. It certainly indicates in-depth knowledge of Roman Latin (in contrast to Medieval or contemporary Latin). As Nicholas says, it also implies a high degree of humanistic awareness. While it takes talented Latin scholars to identify the significance of a tiny clue like this, it is by assembling such small insights that we are beginning to better understand the illusive character of Cecil Calvert.

Today Oxford was beautiful with mild temperatures and sun. And it offered some curious experiences. My apartment (or flat as the Brits call them) is located adjacent to an ancient stone church named St. Thomas. This picture shows it from the apartment window back in January.

Although much altered, this church was established in 1141 by the adjacent Osney Abbey.

Over the centuries, it has been expanded and modified but still retains its basic medieval form. Along the south wall is a fascinating 14th-century priests’ door with five layers of impressive wrought iron scrollwork.

Deciphering the architecture of buildings like this is a major challenge as there have been so many changes over the past 900 years and old elements survive alongside or mingled with those installed by the Victorians.

But what I really want to mention is not the building but something it contains. St. Thomas has 10 bells in its tower that are considered by many the finest in Oxford. On Sundays and several evenings during the week, these bells are rung for one to two hours. We forget about the importance of bells and other sounds in the past, but bells were central parts of life. They summoned worshipers to services, marked time, tolled for the dead, and were rung in emergencies. For example, a surviving document tells us that someone was paid to ring bells at St. Dunstan’s church in London for George Calvert’s death and burial. While I have been here, the St. Thomas bells do chime on Sunday mornings for services but they are also used by a group of volunteers to create beautiful music. Initially, it seemed like just ringing, and was a bit annoying, but over the past months my ears have become more attune to the truly remarkable complexity of the music that is performed on these “instruments.” I met the ringers this afternoon and thanked them for the fine performance. They travel to various churches or chapels around Oxfordshire and beyond for the pleasure of ringing. And the British have bell ringing contests. So part of their activity today was practice but mostly as they said, “It’s just for the joy of ringing.” A few US cities like Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York have bell ringing groups but nothing like the British. As one walks about Oxford, you hear bells from college chapels or churches regularly. Such sounds are a part of daily life in this community today, as they have been for the past 1000 years.

As with most English churches, St. Thomas is surrounded by many tomb stones, most dating from the late 18thinto the late 20th century. There are probably 17th century examples but time has eroded those stones so as to make them illegible. But I did find one particularly poignant survivor. Mounted on the church wall is a carved stone marker with three skulls.

It tells a sad tale of a William and Joan Westberry who, over a seven year period in the 1680s, lost in rapid succession their three daughters ages 2, 3 and 4 years. Markers for such young children of the non-elite are rare from this period and this one serves as a good reminder of the high frequency at which children died during the 17th century, both in England and America. The Westberrys were going through their grief at exactly the same time, 3000 miles away across the Atlantic, another family was experiencing the passing of their young daughter. This baby was a Calvert and while we do not know her name or if she ever had a grave marker, she was given an elite burial in a tiny lead coffin inside the Brick Chapel at Maryland’s capital.

After visiting the Church, I continued the walk to try and see if any remains of the medieval Osney Abbey could be found. This was the largest and most wealthy monastic complex in Oxford, closed and demolished by order of Henry VIII. Today, it appears that there is only a small part of one building that survives, at least above ground. Adding to the destruction was placement of the main railroad line through the heart of the Abbey in the 17th century. The apartment complex where I dwell is located within the former abbey compound on a road still called Osney Lane.

My guess is that the apartment complex stands in the vicinity of the huge monastic church, the largest in Oxfordshire at the time. This conjectural picture gives you a sense of the scale of this massive religious complex ca. 1520. Little St. Thomas church is located on the left side of the illustration (No. 60) and the equally ancient Norman earthen mound I have discussed previously is shown in the background.

This picture came to my attention quite by accident. As I was walking through the cemetery that now occupies a large part of the old Abbey grounds, a man was exercising his very friendly dog. We struck up a conversation and he mentioned the existence of the conjectural drawing. He then departed but returned 10 minutes later, saying he had something I might want to look at. It was the drawing you see here. He was most kind to have made this effort. Also in our initial conversation, I had mentioned that I am an archaeologist. So he next proceeded to totally amaze me by pulling from his pocket what he described as “my big archaeological find.”

It is a complete Roman earthenware vessel nearly 2,000 years old. Found not far from Oxford, it is the first intact Roman vessel I have ever been able to actually hold and I am the first archaeologist to have ever seen it. The form is right for the first to third century A.D. and it is an oil vessel. One never knows what a casual conversation at Oxford might turn up.

Speaking of Romans, this past week was the International Marmalade Competition. The link is that this quinticential British food was actually introduced to Britain by the Romans. They made a dish of quince and honey called melomeli, from which derived the modern name of marmalade. For the competition, there were 300 professionals and 1,400 amateurs entering their creations. Entries not only came from across England, Scotland and Ireland but Australia, Canada, and Singapore. Marmalade making has long been an annual home activity in Britain, with family recipes prized and passed down over the generations. But you can also find a very wide assortment of marmalades in the grocery .

This shows just one part of a long shelf that has many varieties offered for sale. While curry and stir fry might now be popular, marmalade is part of an older British cultural and food heritage. And there is even a special Oxford version that I have not yet sampled.

If you are really into this subject, I suggest The Book of Marmalade by Anne Wilson for both the history and some wonderful recipes you too can try and maybe improve upon.

Addendum

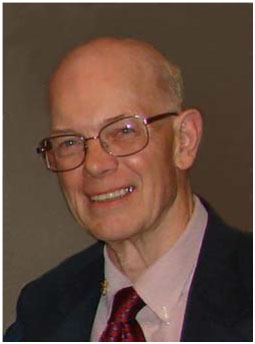

After completing the above, another sad message arrived announcing the passing of Dr. James Patrick Jarboe. Dr. Jarboe served as a Historic St. Mary’s City Commissioner, was chair of the Research Committee for the Commission and also long served as a board member of the Historic St. Mary’s City Foundation and as its Chair. Pat was a remarkable man who dedicated his life to medicine, community, church, and family. He along the McCoy family were key to the entire 1660s Brick Chapel reconstruction project. Pat and his wife Margaret made the first major donation to spur the fundraising campaign. Now it is left up to us to raise the final funds and complete this important project, both in honor of Maryland’s founders and this amazing man. Dr. Jarboe was highly intelligent, generous, hard working, humble, faithful, and possessed in abundance two qualities that are increasingly rare today –Charity and Wisdom. Few have given as much over the decades to Maryland’s first city and we have lost a true friend.

Requiescat in pace!