Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

Henry M. Miller, HSMC Director of Research

This blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

December 9, 2011

The year has flown by and it is time for me to fly back across the Atlantic for the holidays. While they have no Thanksgiving Day in the UK to unofficially mark the beginning of the Christmas season, the spirit of the holiday begins to appear in mid-November. The real mark of the beginning in Oxford is an annual festival called Christmas Light Night. Since it will likely be the only opportunity I ever have to participate, I left the library and took to the streets after dark on December 2, explored the events of that night. Main streets are closed off and they become a carnival ground with rides for children, vendors, and special offerings of entertainment. You can see here the colorful nature of the night.

Many thousands of people crowded onto the wide streets, all in good cheer during this public event. A variety of musical groups performed Christmas songs and many in the audience sang along. The key feature was a parade of hundreds of school children. They marched through the city’s winding streets, carrying glowing white paper devices.

Using the theme of the 12 Days of Christmas, illuminated swans, turtle doves, maids milking, drummers drumming and other representations of the assorted gifts featured in this well known song are carried along in the procession. Several are shown here.

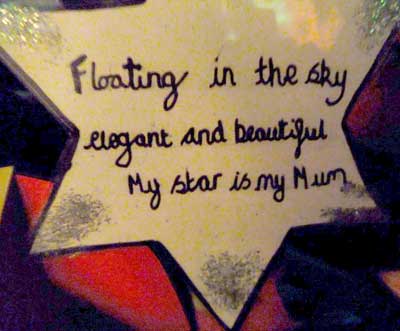

There is also an Oxford practice of grade school students making Christmas Star cut outs and writing a poem or verse on them. These are then displayed on a bamboo “cross” made for the season.

For 9 or 10 year olds, some were quite lovely and I show you just one example from a child that is most endearing.

One of the things I always find intriguing are the foods associated with the various special events and seasons. We all have foods that go with certain seasons of the year or holidays. Some are specific to a family or one community while others are more widely shared, like our Turkey and dressing on Thanksgiving. So I was most eager to see what festival food would be offered for this event. There were real chestnuts roasting on an open fire for sale, and vendors presenting a wide array of items from honey and baked goods to venison and duck sausage, local cheeses, and hot chocolate spiked with Baileys Irish Cream.

Perhaps most popular were a pair that have long had a prominent place in British Christmas celebrations – mulled wine and mince pies. Of course, I had to sample both and they were quite nice.

One puzzle was a sign over a booth with a long line. Inspection revealed that they were selling cotton candy, but in England, it is called Candy Floss, something I would associate more with tooth care.

There are also Christmas trees all over in malls, the courtyard of the Bodleian Library, even in the street. One stands on Broad Street, right outside the doorway into Balliol College, and at night it is most attractive.

This is now a part of the Christmas tradition in the UK but definitely not in the 17th century. And I find it rather curious that this street tree is located very near the location of a cross set into the pavement .

This cross marks the place where three Protestant Martyrs (Bishops Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley (16 October, 1555), and later Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (21 March 1556)) were burnt at the stake for heresy during the reign of Queen Mary. This is a bit of a strange juxtaposition and one can only speculate as to what these men, who were opposed to idols and “popish” ornaments, would have thought about a pagan custom that became a German Catholic and Protestant Christmas tradition being practiced in England, a few paces from their execution site. Legend has it that fir trees with a triangular shape were first used by missionaries in Germany to represent the Trinity, and the tree became associated with Christmas. However, the use of trees goes much farther back in time among the Germanic peoples. The tree at Christmas became widely used in Germany and surrounding countries during the 16th and 17th centuries. English decoration at the time used holly, ivy and other evergreens. While the use of a Christmas tree was brought by the Germanic English Kings in the 18th century, George I, II and III, and there were palace trees, it was not widely copied by the English people. What really changed their minds was a 1846 picture on the front page of the Illustrated London News. It showed the popular Queen Victoria and her husband, the German Prince Albert, standing around a decorated Christmas Tree with their children. Others soon began to imitate the Royal couple and the tree tradition became a solid element of English culture. In the United States, the German settlers had brought this custom with them when they immigrated in the 18th century but it only became generally popular in the 19th century, perhaps spurred by massive German immigration and the popularization of this idea in England.

So the Christmas tree was definitely not a part of 17th-century Maryland practice. Another change from the 17th century is the commercial focus of Christmas that it so dominant today. During the time Maryland was young, the season was a time of gift giving, but Christmas day was primarily for religious observance of the birth of Christ, not presents. The medieval use of the Yule Log was likely carried to the new colony along with other practices associated with this holiday. Puritans opposed festively observing the holiday and its celebration was forbidden in England during the reign of Cromwell. Many objected to this and the Restoration in 1660 saw Christmas celebrations joyfully return throughout the country. Our So our 17th-century ancestors would be puzzled by the way we now celebrate Christmas. This is good example of how traditions can gradually change with time, incorporating new ideas and practices.

With the holidays soon approaching, a new class to prepare, and a paper to write for a session I am chairing at the international Society for Historical Archaeology conference in early January, there will be a hiatus in the blog until I return to England early next year. It will be a year of discovery and diving more deeply into English archives, pursuing the many stories of early Maryland. I leave you with the picture I jam seeing out the window of the airplane, as we wing our way toward America.

Till the New Year of 2012!