Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

Henry M. Miller, HSMC Director of Research

This blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

October 10, 2011

In walking around Oxford, one is continually encountering ancient things and interesting people. Vibrant yet enduring is perhaps a good description. One of the older things I walk by daily is the motte (earthen mound) of a Norman castle built in 1071 by a Robert D’Oiley .

The Motte and Bailey were a combination steep defensive mound and adjoining flat area or bailey enclosed by a wall and ditch. This was often the first type of defensive work built and traces are still evident in many locations, such as within Windsor Castle. They were widely used from the 1000s to the 1200s in both England and Ireland. Many were soon replaced by stronger stone fortifications. Next to the Oxford motte is St. George’s stone tower, probably built before 1100 as part of a church.

As in many other places in England, the Normans were energetic builders. This tower also formed part of the city wall. It became part of the city’s defenses during the English Civil War, when Oxford served as the nation’s capital for King Charles. If Cecil and Leonard Calvert came to Oxford during that war, they may well have seen these two structures. One of my many research goals is finding the evidence for Cecil, Anne, and Leonard Calvert, and Anne’s brother and nephew’s presence in Oxford during that tumultuous period. Her nephew Henry Arundell appears to have lodged at Merton College, where Queen Henrietta Maria (Maryland’s namesake) stayed. Following the capture of the city, much of the defensive works were destroyed by the parliamentary forces. Oxford Castle became a jail and this function continued all the up to 1996. Today it has been converted into a tourist attraction offering tours, a nice range of restaurants, and a hotel. In the conversion, the developers were obligated to retain much of the original fabric, including the cells. Now, for a tidy sum, you too can lodge in one of these old cells to have a “prison experience”, although one considerably more comfortable that of its previous occupants.

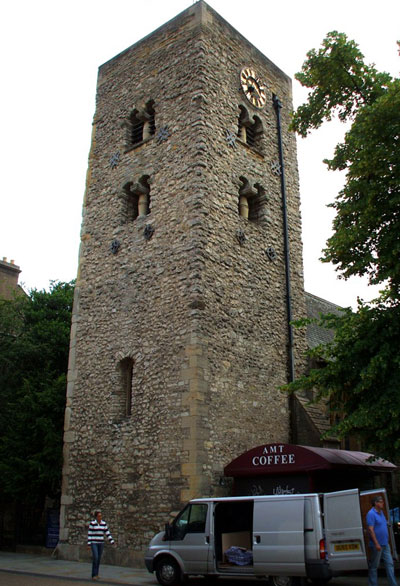

The oldest surviving building in Oxford dates before the arrival of the Normans to England in 1066.

Known as St. Michael’s tower, it was built by the Anglo-Saxons between 1000 and 1050 as part of a church. It marked the corner of the north gate into the city throughout the medieval period. While still a church today, most of it was “restored” by the Victorians and a fire gutted the interior in the 1950s. But the tower is largely unchanged and it remains the most prominent symbol of the Anglo-Saxon origins of Oxford.

From the top of St. Michaels, one has a nice view of parts of Oxford, especially the street known as Cornmarket.

The term comes from the medieval usage of the area by grain merchants and it is one of the major commercial centers and gathering places in the city today. CMRS is less than a 2 minute walk from this street, attesting again to its superb location. Directly across a narrow street from St. Michaels is an equally notable edifice – the “New Inn.”

It is three surviving parts of an original five part structure that began as an inn. The half-timber architecture shows it has considerable age but how old is it? Tree-ring dating of its timbers provided the way to answer that question.

Specialists have perfected the use of tree growth rings for timber dating in all parts of Britain and much of Europe, and it provides a key tool in assessing not only standing buildings but many archaeological sites. In particular, excavations along waterfronts in London, Southampton and other port cities have revealed buried timber crib works, originally built to hold fill for making land and extending the waterfront outward. The picture here

shows some of this archaeology on Trig Lane in London in the 1970s, where they found amazingly well preserved lines of timbers from multiple episodes of land making (acknowledgement and thanks to the Museum of London). Using their knowledge of tree ring sequences, the specialists precisely dated the years of construction, which here ranged from the 1230s to the 1520s. Not only did this provide new insights into the sophistication of Medieval woodworking skills, but the artifacts in the fill behind them could therefore be accurately dated to that same period. Such tight time control allowed thousands of previously uncertain artifacts to be give solid dates, thereby revolutionizing understanding of how medieval life and its materials culture changed over time. An old friend, Geoff Egan, wrote multiple volumes about Medieval artifacts using this very evidence. We too use tree ring dating in America, with a very good example being the Mackall barn at St. Mary’s City, dating to 1785. What about that building in Oxford. It turns out that it was constructed in 1386 or early 1387, making it one of the oldest wooden buildings to survive in the city. As a close inspection of the picture will reveal, the current use of this fourteenth-century structure to sell 21st-century mobile phones makes for an interesting contrast.

My efforts are still partially focused on a grant proposal and the new visitor center exhibit design, but some work on early Maryland research is also underway. But pleasant interludes do occur. Yesterday, I had a surprise visit from Maryland friends, Marilyn and Tom Maday, who are in England for a wedding. They came to Oxford for a few hours in the afternoon accompanied by a delightful British friend of the Madays, and I was able to meet up with them. We celebrated at a particularly notable establishment – The Eagle and Child pub.

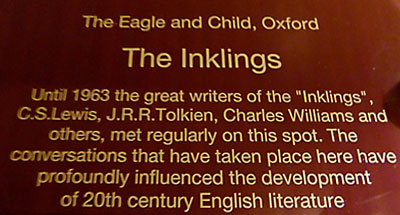

While of 17th-century origin, it is most famous for a group of people who met there weekly between 1939 and 1962. These were writers who, over pints of ale, read and discussed manuscripts of their current literary projects, seeking advice and suggestions. Known as The Inklings, they included C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien and Charles Williams among the 10 to 12 regulars. It was here that works such as The Lord of the Rings, Out of the Silent Planet, Mere Christianity, and All Hallow’s Eve were first presented to an audience. We were very lucky to find a table in the exact space where The Inkings would meet, a place marked by a variety of plaques and memorabilia of these most famous patrons

Oh, to have been a bartender listening in on those fascinating discussions.

I conclude with a peculiar entry on local culture. In the Oxford shopping malls, an intriguing service is offered to customers. It consists of placing one’s feet in tanks of water occupied by numbers of small fish. These fish proceed to nibble at one’s feet and toes. On Saturdays, I have often observed every tank to have people undergoing this “treatment”, which they claim is pleasurable.

However, since it costs 10 pounds ($16.00) for a ten minute experience (or a bargain $45 for half an hour), they will not get at my toes or money, I assure you. Its popularity is rather surprising to me, but I understand that the practice is now crossing the Atlantic, so you too may soon be able to have such an experience at a shopping mall, if you dare.