Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

Henry M. Miller, HSMC Director of Research

This blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

January 30, 2012

It has been busy since my last post. Historic St. Mary’s City (HSMC) was well represented at the Society for Historical Archaeology annual conference the first week in January. Held in Baltimore this year, the conference attracted nearly 1,400 people from around the world. We had a session on St. Mary’s City and the Atlantic World, with papers on topics spanning 400 years of time and including talks on Calvert site research in Ireland and Newfoundland. Our discussant was the first founding archaeologist for the museum, Garry Wheeler Stone. And the very first HSMC archaeological curator, George Miller, received the highest honor of the society – The Harrington Medal – for a life time of contribution to the field. As part of the award, current curator Silas Hurry gave a most entertaining George “roast” at the banquet. HSMC was also honored with the Society’s special Award of Merit, given for the four decades of sustained archaeological research into Maryland’s history. It was my honor to accept this award on behalf of the museum and the many hundreds of people who have contributed over the years to our exploration of St. Mary’s City. In an interesting coincidence, it was given by the SHA president William Lees, who was a fellow student with me at Michigan State University way back in the 1970s.

Historical archaeology is a relatively small field of scholarship that is undergoing dramatic growth.

Immediately after the conference, we returned to St. Mary’s City and on Sunday, 8 January, Irish archaeologist Dr. James Lyttleton gave an excellent presentation on his recent discoveries at the site of Lord Baltimore’s manor of Clohamon in Ireland. Then some quick packing, goodbyes, and a return to Oxford, where I instantly proceeded to get sick for three days. But now efforts have resumed on varied topics related to early Maryland and its residents. One involves more visits to the archives of Trinity College to record information regarding George and Cecil Calvert and John Lewgar. Not only is it fascinating to find the references to them in the various original documents, but discovering the classmates they would have lived with while there may provide valuable leads in further archival exploration.

I was further given permission to examine the 16th- and early 17th-century Oxford University archives with particular focus on the information they hold about George Calvert. Back in 1931, an article was published about George’s Oxford years in the Maryland Historical Magazine. While a good read, it totally lacks any references, so one is left to speculate on what is based on actual evidence and what is imagined. Looking at the original large volume of University records dating to the years 1595 to 1606 has revealed several statements about George and the events associated with his graduation in 1597. All is written in Latin which is a problem for me but my co-worker here, Dr. Nicholas Crowe, is translating the relevant sections. The Library did give permission to take photographs of these passages but the rules regrettably do not allow me to show them to you.

I studied this unique University record book dating from the late 1500s in the Duke Humphries Library, resting it on wooden stall dating to ca. 1600 in a room that was completed in 1485. One really feels history in a place like that. The Duke section is now part of The Bodleian Library, an internationally acclaimed research facility where I spend as much time as possible. Hence, a brief tour and history of this amazing place is in order.

The first real library of the University was provided by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, in the mid 1400s. The University had been constructing a new Divinity School in ca. 1420 and the Duke’s donation of 2,000 volumes prompted the adding of a second floor on the Divinity School to house the books. This picture shows a side view of the Divinity School, with the library section above having smaller windows.

As a superb example of Gothic architecture in Oxford, it features elegant window tracery, buttresses with panels, the roof line with battlements, and each buttress caped with distinctive pinnacles or pyramids that were copied again in later Oxford architecture. In the center is a door installed by Sir Christopher Wren in 1669. Given this date, some of its construction details had an influenced on the design of the reconstructed chapel doors at St. Mary’s City. What is impressive about the Divinity School is not the outside, however, but the amazing interior. One enters through the main doorway for the Bodleian Library. Then, ancient double wooden doors open into a vast space capped with a remarkable vaulted ceiling.

Constructed by master craftsman William Orchard, his initials are found carved on one of the arches. Architects have described it as one of the marvels of Oxford.

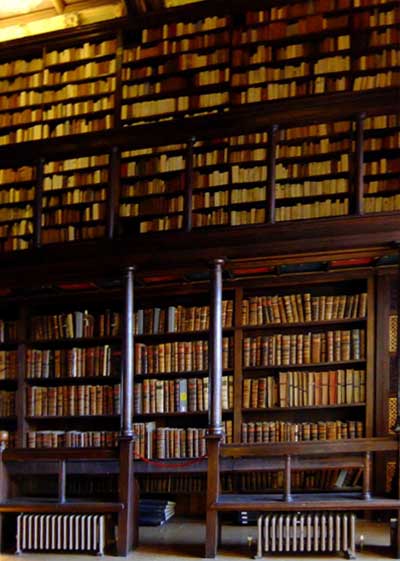

Upstairs is the Duke’s library, which has its original 1470s ceiling colorfully decorated with varied seals, symbols and crests. Unfortunately, photos are not allowed here. It is a secure area where scholars are allowed to examine the most delicate and priceless volumes the library possesses. To get there, one climbs the stairs to the second floor and then enters the Duke Humphreys area through a 1612 addition called the “Arts End”. It has ancient volumes chained to the walls on the lower level. Due to their great cost, this was the standard way of protecting a library’s holdings in medieval times. But on the balconies above, books are stored on shelves along the walls without chains; reportedly one of the earliest applications of what was then an innovative book storage method that we all habitually use today.

All of the woodwork you see here dates to ca. 1612.

The main Bodleian Library was started by Sir Thomas Bodley. Unfortunately, during the Reformation, most of the original books given by Duke Humphrey were dispersed or destroyed, so Bodley began a new library in 1602. Construction of a proper building for the University books began in 1613 under Bodley’s inspiration. It took the form a large square called the School Quadrangle and was completed in 1624. Three stories in height, the north and south sides are relatively plain, the west end into the Divinity School is the main library entrance today, with the door surmounted by a large seven part window, and the east end has a tower that is the formal entrance into the quad. The current library entrance was actually built on the front of the Divinity School in 1610-1612 to provide more room for the library above, and copies the original style of the 1400s structure.

It features four tiers of long narrow, honey-hued stone panels, capped again with an embattlement and pinnacles of the same form as on the Divinity School. Projections in the corners are the stairways. From the upper part of the stair, you can get a close-up view of the complex carving that makes up the distinctive pinnacles of Oxford.

Opposite this façade is a unique tower five stories in height.

This is unparallel in England, being the largest, and is an early example of Italian inspired Renaissance architecture. Depicted as one rises up the tower are the five classical architectural orders in its columns — Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite. Elaborate decoration accompanies each section but the focal point is the fourth level (third floor in British floor numbering), where a statue of the then reigning King James I, is found in a niche.

On his left is a statue representing Fame blowing a trumpet in tribute to James while on the right is a kneeling figure depicting the University. James holds a book and I suspect it may be the famous bible he commissioned. One wonders if George and Cecil Calvert attended the dedication of this tremendous facility.

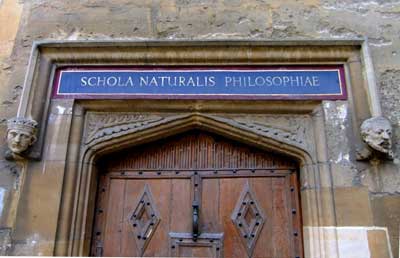

Around the quad on the ground floor (the first floor in England is what we call the second floor) are doorways into varied original schools. Above the doors are painted the names of these schools – Astronomy, Geometry, Grammar, History, Language, Law, Logic, Medicine, Metaphysics, Moral Philosophy, Music, and Natural Philosophy.

Each doorway is accompanied by decorative stone carving and in many cases the doors and wrought iron hardware are original. Construction details found on some of these also helped us with the design of the Chapel doors.

The Bodleian holds millions of volumes and manuscripts and part of the reason it became so rich in books is an agreement that Thomas Bodley struck in 1610 with the Stationers’ Company in London. The Stationers’ registered published books and Bodley saw to it that a copy of every book printed in England would be deposited with the Bodleian. His enduring contribution to scholarship and education is amazing, emerging from a Renaissance sense that a sound grounding in classical skills and literature would create virtuous citizens. The disciplines identified on the doorways around the Bodleian Quad reflect the breadth of intellectual study and curiosity in the seventeenth century, a breadth combining both medieval and renaissance scholarship. Given his love of learning and foresight for future generations, Bodley deserves much credit. It is thus highly appropriate that his memorial in the Chapel at Merton College here in Oxford shows Bodley flanked by stacks of books and classical figures.

It is a real privilege to be able to do research in this incredible place. One can find a reference to some obscure late 18th-century publication and only a day later be looking through it. Part of the fascination is that there are so many unexamined things that might have relevance to Maryland. For example, discovering that the Bodleian has all the surviving archives of the famous Irish family – the Talbots – to whom the Calverts were married and for whom a county in Maryland is named demands investigation. These records could hold some valuable new information. The search continues and for now I will leave you with the view of what I can see out the window from the study carrel on the top floor of the Bodleian.