Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

This blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

March 25

Happy New Year! This is the day that Maryland’s 17th -century settlers celebrated the start of the new year. That continued up until 1752 in England, although most of Europe had adopted the new Gregorian calendar we use today in the 1580s, with New Years being 1 January. Using different calendars is a source of potential confusion when studying early historical documents, because 10 February could be in the year 1634 in one place, but 1635 in another. We assume most of Maryland’s founders would have started their year on 25 March. But what about people like Andrew White who were educated in Europe and would have employed the new style that the Catholic church followed? It could be confusing to them and to us. Remnants of this endure here. While most shop rents in the US are paid monthly, payment for High Street (i.e. Main Street) stores is due quarterly here, with 25 March being a due date, as it was far back into Medieval times.

March 25 is also the Feast of the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary. It remains an important day in the Christian calendar and for that reason, as well as it being the English New Year, the Catholic settlers on the Ark and the Dove celebrated the first mass in the new colony on that day. Currently, we know it as Maryland Day, designated by the state to recognize and remember the founding of Lord Baltimore’s colony in 1634. This is taken to be the start date of Maryland. But when exactly does a colony begin? Could it be when the royal charter was issued, the first ships departed from Europe with the initial settlers, or when they arrived in the new place? Or is a formal ceremony is required for taking physical possession of the land, erecting monuments and raising their country’s flag? On the other hand, does a colony begin when the settlers actually come ashore and started building structures to physically mark their presence? This is a significant issue and one chapter in a book I am working on is required to explore this key question, a question that is far more challenging than it might at first appear.

The Virgin Mary obviously has a prominent place in Maryland history, but so too here at Oxford. The university was in many ways centered upon a medieval building called the University Church of St Mary The Virgin.

It is both an active parish church and part of the University. The first University building from the 1250s used for meetings of the faculty or congregation as well as worship stood here. It was enlarged with a new church. The impressive tower of was started in the 1290s with construction of various elements continuing until ca. 1320. It offers one of the most impressive medieval spires in England. To the left of the tower is a three window addition. A careful inspection will reveal that it has an unusual feature for a church – chinneys sticking out next to the church wall. It is called the Convocation House, the first real office of the University. There are two floors in this addition with the first floor originally meetings of the University Congregation while the second floor was the first library, the earliest University library in England. This use ended when the Duke of Humphrey library opened in 1488, now part of the Bodleian. St. Mary’s displays all the classic elements of Gothic architecture with stone buttresses, pinnacles, battlements, and elaborate multi-part arched windows in the perpendicular style.

Another image shows some of the fascinating carved stone figures on the tower.

Other sections of the church were built or modified in the late 1400s, typical of the complicated history of these ancient churches.

On the south side is a much later addition of 1636-1637. This porch has many classical elements with its elaborate twisted columns and a niche holding a statue of the Virgin Mary .

A wonderful architectural addition, drawing it’s inspiration from Italy and reportedly built for the sum of 230 lbs sterling. There is a tragic story linked to this porch. Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud ordered the porch to be built as part of his efforts to reform the Church of England, and the incorporation of the statue simply emphasized the namesake of the church. Laud sought more uniformity in the church, greater use of sacred ceremony in services, and strongly opposed the growing radical theological ideas of Puritans. Our John Lewger (builder of St. John’s) served under Laud while he was an Anglican minister at the village of Laverton in the early 1630s. When political tensions between Charles 1 and Parliament reached the boiling point in the early 1640s, Laud was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower. Finally brought to trial in 1644, this porch with its statue was used as evidence of his “Popish” tendencies.

Parliament sentenced him to death and he was beheaded on 10 January 1645, in part because of the “idolatrous” inclusion of this Mary statue on a church dedicated to Mary. After Parliamentary forces captured Oxford during the Civil War, soldiers shot at Mary’s statue with their muskets and it still shows these bullet scars from the Roundheads. Such was the intolerance of belief that prevailed over England at the time.

While altered by the Victorians, the interior of St. Mary’s church retains many of its original elements.

It has much relevance for us since this was the scene of all major Oxford University functions up until the building of a new theater called the Sheldonian in 1669. It is from St. Mary’s that George Calvert and John Lewger received their B. A. degrees, Cecil Calvert attended debates here, and in 1605, George was given an honorary M.A. degree within this church. It is one of the few buildings in Oxford that each of them would be able to immediately recognize if they returned today. Well, let me slightly modify that.

Today, the church is shrouded in plastic and scaffolding. It is undergoing its first major renovation since the 1890s, paid for by funds raised through the English lottery. (Perhaps Maryland should dedicate a portion of its lottery funds to such vital heritage projects within the state, too?). While the repairs and cleaning are underway, the church is understandably closed but only in Oxford would they decide to label this period of renovation “a Parish Sabbatical.”

Not only has this building been central to the University’s history, but it also has been the sight of many religious controversies and notable debates. It is here that the Anglican bishops Hugo Latimer, Nicholas Ridley and Thomas Cranmer were tried for heresy in 1555 and later burned at the stake. The 1555 trial required a platform to be built and one of the stone columns had to have a notch cut into it to support the platform.

It is still there, physical evidence of a single event sparked by the Reformation that occurred 457 years ago. In the 18th century, John Wesley gave sermons here while he was on the spiritual path to founding the Methodist church.

And from this wooden pulpit of ca. 1800 century date, John Henry Newman (now St. Newman) delivered moving sermons that sparked the famous 19th-century Oxford Movement in the Anglican church. Many notable 20th century figures have also spoken from this pulpit including Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

But one marker here has particular relevance. Oxford was the site of much religious violence in the 16th and 17th century, with both Protestants and Catholics being executed for their religious beliefs. Maryland’s novel approach to liberty of conscience was not accepted opinion during this period, making it all the more remarkable. Thus, it seems highly appropriate that a recent monument has been ecumenically dedicated in the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin to all the martyrs associated with Oxford.

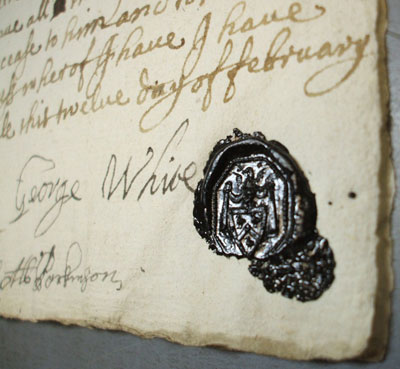

Research has recently been focused on the White family of Essex. This line is of great importance for Maryland because the man who probably devised and laid out the design of St. Mary’s City, Jerome White, was a member. His uncle Thomas shaped the curriculum that Philip Calvert studied in Lisbon and almost certainly influenced the spiritual and temporal outlook of the Calvert family. I have tracked down their family pedigrees and located their estates in Essex. There were three main properties: Hutton, Runwell and Thundersley. Each were parishes but also had manorial status and there is a map of Runwell manor from the 18th century that might contain information about its former occupants. I hope in the next few weeks to rent a car, and visit these locations. While there may not be any buildings still standing, churches could still hold monuments and other traces of their lives in this part of England. I have also found that the family is noted in “visitations” by government officials of Catholics or recusants in the counties of England in 1552, 1558, 1612 and 1634, thus providing key evidence about their families. There are also documents such as wills that need to be examined and transcribed, as they can yield valuable new insights about family connections and properties. Jerome’s brother George left a will in the late 17th-century that I have examined. Along with his signature is the still attached and well preserved wax seal from a signet ring George owned that carried the family crest .

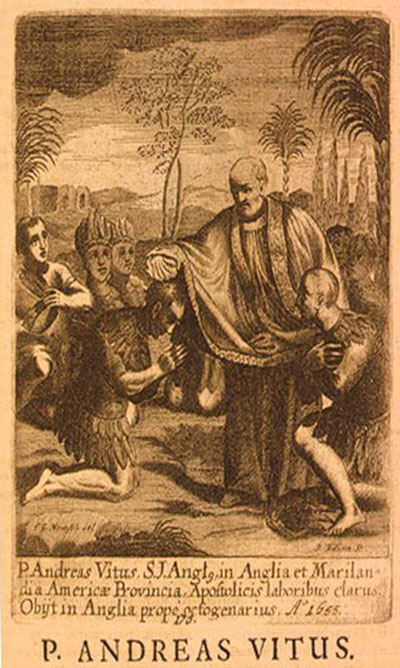

And there is a huge question regarding this family and Maryland. Was Father Andrew White related to them? As the Apostle of Maryland, Andrew White was essential to the effort to establish the colony and to our understanding of its first years.

This picture is the only one of Andrew White, although depicting him with palm trees in Maryland makes one question the accuracy of the illustration. As scholar Leo Lemay wrote in his study Men of Letters in Colonial Maryland (1972), “The biographical facts of Andrew White’s life are fragmentary, scattered, and sometimes contradictory.” Unfortunately, that assessment is still accurate 40 years later. There is the suggestion that Andrew White was born in 1579 and probably came from London, but nothing more is known about him until he entered Douai College in Flanders in 1593. Thus, another goal is to try and uncover more clues about this hugely significant figure in Maryland history. Work on the White family of Essex is one approach and a trip to the British National Archive at Kew will be made in the near future to collect other essential evidence.

Cheers.