Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

Henry M. Miller, HSMC Director of Research

This blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

May 30, 2012

On my nearly daily walks to the Bodleian Library, much intriguing architecture can be observed. Some is nearly a thousand years old while other buildings are but a few hundred years or even younger. But of all these, one stands out as the most common tourist image of Oxford. It is a library that is part of the Bodleian and called the Radcliffe Camera.

This building is at the center of the University. It sits in a large cobble stoned and grassed square defined by St. Mary’s Church on the south, the Divinity School and Bodleian Library, to the North and two colleges on the East and West sides. Dr. John Radcliffe left 40,000 pounds sterling to build this structure and design occurred in the 1730s. Construction began in 1737 and was completed twelve years later, the first circular library in England. Its name seems rather strange – a Camera? The term comes from the Latin for Rotunda or drum which is the architectural essence of this building. It is capped with the drum that has windows and an impressive dome. Eight pairs of arched opening and niches are found around the bottom, while the upper portion has pairs of columns, topped with a balustrade and stone balls. Lead covers the sides of the dome. The niches at the bottom provide excellent resting places where I typically have a sandwich for lunch.

Today one enters through the stairs you see in the top picture, although these were not original and only added in 1863. A lovely spiral staircase inside takes you to the lower floor or up to the main floor. This upper library is absolutely magnificent. There is a large open central area bordered by eight pairs of piers that support a gallery about half way up. The gallery runs around the entire building

The stone carving is beautifully executed and the statue you see in the niche here is of the donor, XXX Radcliffe. But what I find most impressive is the dome that is decorated by stucco. The plasters did a wonderful job here and it is a pleasure to gaze up at the elegant geometrical form. The Camera contains many volumes on Theology and History,(along with other topics) and is an inspiring place to study, as well as being the most photographed building in Oxford.

The west side of the square here is formed by a college named Brasenose. Founded in 1509, its gate tower of ca. 1512 faces the Camera. There have been numerous repairs and modifications but the basic form is original. And the wood door is definitely old, assembled with wrought iron hinges and hand forged nails.

As I have noted earlier, college entries tend to feature religious statuary and Brasenose is no exception. If you look at the image below, you will see two bishops and at the top the Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus. I especially like the row of carved human faces at the bottom of this picture.

And the Tower also features the college crest, two beautifully carved angels holding a crown with a flanking hound and griffin below. They still bear evidence of gold and faded red and blue coloring. One of the great joys of walking around Oxford is discovering such decorative elements on various buildings, often as finely executed as this Brasenose crest, or even more extravagant. These are important parts of the architecture, not something they considered superfluous or unnecessary “extras” as many contemporary architects seem to view them today.

As you enter the college, one first encounters the “Old Quad”. It has 1500s housing for students and very prominent rows of dormers at the top that were added around the time Maryland was being founded. There is also a prominent sundial on the wall, but it is a rather late addition, being put up in 1719.

Brasenose is one of the Oxford colleges that have direct Maryland connections. A graduate of Brasenose was a young Yorkshire man named Lionel Copley. He matriculated here in 1665 and later entered the military, serving as a garrison commander at the port of Hull in the 1680s. In the so-called “Glorious Revolution” of 1688, he sided with Dutch King William and Queen Mary against her father King James II. It was this action and connections that prompted Queen Mary in 1691 to appoint Sir Lionel Copley as the first Royal Governor of Maryland. Arriving in Maryland in 1692, Copley took over the government from the men who had led the rebellion against Lord Baltimore. And he did so in a building many of you know – Van Sweringen’s Council Chamber. It was here that he read the royal proclamation making him governor to the Maryland Assembly and here that he held the first meetings with his council. This notable event in Maryland’s colonial history has been wonderfully captured by the talented artist Les H. Barker for the Van Sweringen exhibit that the National Endowment for the Humanities helped fund. This scene represents Copley holding that first council meeting.

by Les H. Barker. Copyright, used with permission.

Les has painted a wide range of historical images not only for St. Mary’s City sites (Van Sweringen, St. John’s and the Brick Chapel) but for a number of other museums including George Washington’s birthplace. She is a delight to work with and strives to make the images as accurate as modern scholarship and art will allow. To view more of this award winning artist’s outstanding efforts, you can visit Les at http://lhbarkerstudio.com/Pg3.html

Lionel Copley led a troubled administration with much conflict. Upon their arrival at St. Mary’s City, the new governor, his wife Anne and their children moved into the grand mansion called St. Peters Philip Calvert had built at St. Mary’s City. But their time in Maryland was not to be very long. Anne died in March, 1693 and a few months later on 12 September 1693, her husband followed her in death. Perhaps the unavoidable “Seasoning” that all Maryland settlers suffered from in their first year is what stuck down the Copleys. Their passing left young children to be cared for and a superb inventory of the estate was taken. It gives us many wonderful details, such as the fact that he owned a telescope and had a magnificent white horse named Dragon. Dragon was worth four times more than the average Maryland horse so he must have been a fine steed.

But the Copleys are important to us in another respect. When they died, both were buried in lead coffins near the Statehouse at St. Mary’s in 1694. They were placed in a brick vault and forgotten about until the vault was opened in 1799. Sir Lionel was mostly a skeleton but his wife was totally preserved, until fresh oxygen interacted with her remains, rapidly reducing her to a skeleton. We were allowed the opportunity in 1992 to reopen this vault and examine the coffins and remains. The lead coffins are still there, as are substantial portions of the wooden coffins which you can see in the picture below. Evidence collected here gave us invaluable insights about how lead coffins were made, aided us in planning Project Lead Coffins and provided never before available details about the Copleys themselves.

No portrait of Copley is known to survive, so how did Les Barker paint him in the Council Chamber scene. It is not totally imaginary because of our access to the Copley vault. Smithsonian scientist Douglas Owsley was able to made invaluable observations about Copley’s height, body build and facial structure and we photographed his skull. This guided Les Barker in creating the image you see of Copley in the painting. If you visit Trinity Church cemetery at St. Mary’s City today, you can go to the resting place of the Copleys, for their bodies and lead coffins still lay in the brick vault under this marker.

Lionel Copley forms another strong link between Oxford University and Maryland. And visiting his college also gives us some marvelous information about seventeenth-century chapels. The one Lionel worshiped in while a student at Oxford was built between 1656 and 1666, nicely overlapping with the construction era of the Brick Chapel at St. Mary’s City. From on high, you can see the general rectangular form of the structure.

A street side view shows that it has a large and elaborate eastern window in the form of Gothic-Revival architecture. It features flat columns or pilasters, little cherubs, a strongly curved gable, and corner and top pyramids or urns.

On the inside, one finds a small but well decorated Anglican chapel with seating on each side and an altar table at the east end of the structure. But what is most spectacular about this space is the ceiling. Notice the wooden projections from the walls where the ceiling starts. These are called hammer-beams and hanging pendants which are inspired by Gothic architecture.

Most extraordinary is the plaster ceiling. Installed in 1665, it is a fan vault that has lovely painted floral decoration. While the colors are somewhat faded, it remains a most memorable and beautiful space that Lional Copley would be able to recognize today.

One interior element attracted my special attention. It is the wooden pulpit for the chapel. Standing on six legs, it displays panels that have an intriguing perspective decoration. Such a decorative style is seen in several other Oxford Chapels of the seventeenth century as well as found elsewhere. Looking at the panel reminds me of the interior of the Brick Chapel in terms of overall form and proportions. Could this 1660s pulpit be a model for the one we make for the Brick Chapel at St. Mary’s?

A question that puzzled me and probably you is the origin of the name. Was there a Mr. Brasenose who made a huge contribution to start the school? Apparently not. Rather the answer derives comes from an ancient door. On that door was a brass knocker or brazen nose used by the early students that inspired this identity. Today, when you enter the dining hall of the college, you see at the far end of the hall, beyond the high table and centered on the wall in a place of honor, an elegantly mounted object.

It is a 1200s brass knocker that is claimed to be the original from which the college took its name. I am told students traditionally rub its nose when they graduate. Oxford colleges have acquired their names in some unusual ways.

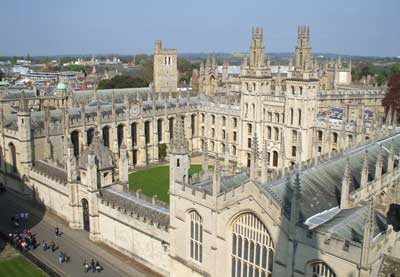

Directly opposite Brasnose on the other side of Radcliffe Camera is All Souls College. It is characterized by many spires that are so much a part of the Oxford skyline. Founded in 1438, All Souls has had numerous additions and its most obvious elements are of early 1700s date, although also inspired by Gothic architecture. This view looking from just outside Brasenose College lets you get a sense of the many spires.

This is even better when you have a view from a higher elevation. Then, the many spires of All Souls and its grassy quad become especially impressive, forming one of the quintessential view of Oxford.

In this view is what some regard as the most famous of All Souls many structures -its twin towers. Designed by the noted architect Nicholas Hawksmoor in 1716, legend has it that these two gothic stacks are the origin of the expression about someone being “In the Ivory Tower.”

So the core area of the city is an architectural delight, with fascinating and historic buildings on every side. So large and close are these structures that on a late winter afternoon, the strong shadow of the Camera dominates the side of the older Bodleian Library.

Oxford is without doubt an ancient and remarkable city and one artifact of its great age is a small seal made of wax. This was impressed and affixed in the year 1191 to the original city charter for Oxford, granted by King Henry II. Called the common seal of the city, it shows the ox of Ox-ford within protective city walls. It is the oldest municipal seal surviving for a city in England.

Seals have been used as official markers for millennia. They still appear on some official documents and linger most commonly today in the impression of a notary republic seal on your important documents. Wax seals were also a compliment to a person’s signature, used to close personal and official letters, signifying authenticity. As with a signature, they reflect the identity of the individual and thus, occur in a wide variety of styles. Often family crests are used but others have more fanciful images. In looking over thousands of original documents in the last year, I have become fascinated by their types and symbolism and photographed many of them for study. Among them is a 1636 seal from Secretary of State Francis Windebank, a colleague of George Calvert and supporter of Cecil Calvert’s efforts with Maryland. As John Krugler has demonstrated, Windebank played a vital role in the success of Maryland, especially during the conflict with William Claiborne and the Virginia interests.

Another is from a remarkable man named Kenelm Digby. Writer, scholar, diplomat, scientist and all around “Renaissance” man, Digby knew George and Cecil Calvert, as well as Maryland’s Surveyor General Jerome White and his Father Richard and Uncle Thomas. Indeed, I have evidence that Digby and the Whites dined together at the English College in Rome. Digby served as Queen Henrietta Maria’s chancellor, and was the unofficial representative of England’s Catholics during Cromwell’s reign. A man of broad talents, he was described as “a magazine of all arts.” This is his seal.

The Lords Baltimore also used several seals on their correspondence and on official documents. I am recording the varied examples of their official markers as much as possible. One discovery a few days ago is a never before photographed seal on a court document. It was personally impressed by the second Lord Baltimore Cecil Calvert In the year 1641.

My next posting will be about sights and discoveries made in the homeland of Anne Arundell – Wiltshire.