Dispatches from Oxford in the Realm of England

Henry M. Miller, HSMC Director of Research

This blog reports the experiences and findings of Dr. Henry Miller while he is on assignment at the Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Oxford, England. From September 2011 to May of 2012, he will be conducting research about early Maryland and its English connections, writing, and teaching. Watch this space for Dr. Miller’s research findings, insights on the remarkable history and nature of Oxford and other places he visits, and curious aspects of living in another country.

November 13, 2011

This is a time when memories are much in the mind. Friday a week ago, fireworks lit up the Oxford sky and fire crackers popped late into the night. Outdoor fires were ignited in various locations. This was Bonfire night, and it, like so much else here in England, has a long history. Specifically, it dates to the early morning hours of 5 November 1605. The event on that night is expressed in a popular rhyme many of you may know:

Remember, Remember,

The Fifth of November.

Gunpowder, treason and plot

We know no reason

Why Gunpowder Treason

Should ever be forgot…

The famous Gunpowder Plot was a scheme devised by a small group of English Catholics, upset at the persecution by the English government and the failure of the new king James I to honor his implied intentions to provide greater freedom to Catholics. Their goal was to blow up the opening meeting of Parliament, killing the King, his ministers, the Anglican bishops, and members of Parliament. By assassinating the leadership of the country, their unrealistic hope was that a Catholic ruler, the King’s daughter Elizabeth, could be installed. To achieve this, an opening was dug from a nearby cellar into the space under the House of Lords at Westminster, and 36 barrels of gunpowder were secretly placed there. The munitions expert was Guy Fawkes, who placed the charges and would ignite the fuses when Parliament began. Involved with this plot were perhaps 15 people, some of whose families later had connections to Maryland. Among them were Thomas and Robert Wintour, hung, drawn and quartered for their roles. A relative also named Robert Wintour wrote a fascinating promotional letter about Maryland that John Krugler has published. Robert later came to Maryland and it is he who first used the term “the Maryland Design.” Father John Gerard was also alleged to be involved, although all evidence indicates he was not. He was a relative of Maryland settler Thomas Gerard.

A secret message about the plot was given to Robert Cecil by an unknown person. This the same Cecil for whom a young George Calvert had just started working for two years before. The letter and perhaps other intelligence led Cecil to order searches and just after midnight on 5 November, Guy Fawkes was found in the cellar and arrested. Here in Oxford is an amazing artifact directly related to this event. It is the lantern held by Fawkes.

This artifact was given to Oxford University in 1641 by Robert Heywood, the son of one of the men who arrested Fawkes; it is now on display at the Ashmolean Museum. Few artifacts had such historical potential. It would have provided the fire that would have lit the fuses that exploded the gunpowder that killed the King and Government. If the plot had succeeded, history would have been very different. George Calvert’s patron, Robert Cecil, and King James would have been killed, and it is unlikely that George would have risen to such prominence. While Virginia may have been established, no Maryland with an English Catholic proprietor would have been created.

Although the vast majority of English Catholics had no involvement and would have opposed the plot if given the opportunity to be involved, it provoked a serious response. Parliament intensified Catholic persecution, added an Oath of Allegiance for all subjects and passed the “Observance of 5th November Act 1605” which required sermons each year about the plot, and by royal proclamation, a special celebration was added to the Anglican Book of Common Prayer called the “Gunpowder Service”. It continued being held annually until 1859. Bonfires where an effigy of Guy Fawkes or sometimes the pope, were burned became associated with the 5th of November. Gradually, the anti-Catholic nature of this event receded and it evolved into Bonfire night, where young children would dress up and ask for “a penny for the Guy” from passersby. Collected money was used to purchase fireworks and the bonfire became more of a social and family occasion. An effigy of Guy Fawkes is still sometimes burned, as I observed in London in 1997. During the colonial era, there is evidence that Guy Fawkes Day was also observed in some of the American colonies, especially New England. With this event, people in England today continue to “Remember, Remember, The Fifth of November” 1605.

November offers other reasons for remembering, however. People young and old here begin wearing a paper poppy on their clothing early in the month.

It becomes most prominent on 11 November and the Sunday afterward called Remembrance Sunday. We in the US called this Armistice Day for many years but then changed it to Veterans Day. Aside from the American flag, we have no unique symbol of the day that corresponds to the poppy. The paper one you see here is typical in England. But I have observed other styles being worn and asked where they were acquired. One group of older men said you can get one in Ottawa, they being Canadians. Another man said his came from Australia. Why do they wear these? The answer is found in a powerful poem written by a Canadian soldier in France in 1915. John McCrae observed the many poppies blooming in the newly disturbed ground of no-man’s-land and over soldiers graves and wrote “In Flander’s Fields”:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

As CMRS Principle Mark Philpott has said, “Thus the poppy comes to be also a striking symbol for our remembrance of the sacrifice and our determination to hold high the torch thrown to us at so high a price.” McCrae inspired this with

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high,

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields

Although Remembrance Day honors all of the soldiers, sailors, airmen and medical corps members who have served, its origin lies in the Great War or World War One. This conflict had a tremendously deep impact upon Britain and the Commonwealth nations. The United States also became involved in that war and lost many men. I remember my own grandfathers who served in France in 1918. The war changed their lives in ways it is impossible for me to imagine. But the scale and depth of the suffering and human sacrifice for England, its Commonwealth nations, as well as France and Germany, was far greater. This was made clear in an article I read that talked about wars. The United State had terrible losses in Vietnam. Over the 12 years of that conflict, 52,000 of our troops lost their lives. But England lost 58,000 men in a single 8 hour period on one day – 1 July 1916 at the Somme. And other days had nearly as many casualties. There was not a town or village in the entire country that remained unaffected. In fact, you will not find a church the country built before 1950 that does not have a memorial plaque listing the dead of that village or town. In some cases, an entire book is displayed with hundreds of names neatly recorded, the pages being turned gently throughout the year so all are recognized. Eventually, over one million people from throughout the commonwealth lost their lives. Thus, the poppy came to symbolize the huge sacrifice for the English and Canadians and ANZACs in a powerful way.

Today, older people universally wear a poppy. Many younger people do as well, although not all. But all are called to remember. On the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, bells ring precisely at 11:00, the moment the guns fell silent on the Western Front. But then there follows a remarkable two minutes of silence throughout the entire country. Radios and television stations go quiet and traffic stops. I was on one of the busiest street in Oxford – Cornmarket – at that moment. Everyone stopped what they were doing. On the adjoining streets, cabs and buses stopped in the road. All stood respectfully for two minutes of silence. No doubt some of the students were clueless as to what was happening but they too recognized it was something significant. To share in this was for me emotionally moving and makes me wish the citizens of the U.S. could respond in a similar fashion on Veterans Day. And this is a special year for the observance of the end of the Great War. That is because it is the first November 11th since 1918 that no living witness to the conflict is with us. The last WWI combat veteran died earlier this year and that monumental event now has passed from living memory into the realm of history.

Today, I attended the official remembrance ceremony held at the war memorial in Oxford.

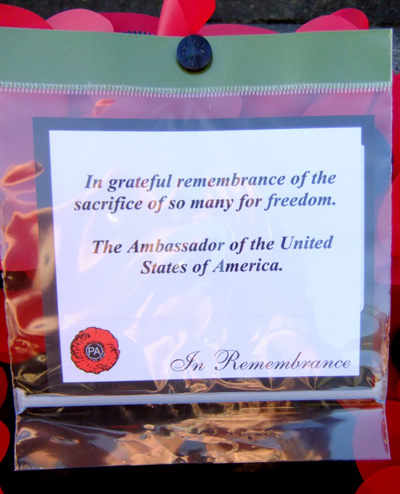

My motivation was that such ceremonies are important and I would probably never again have the opportunity of participating at such an event in England. At 10:30 on Sunday morning, between 2,500 and 3,000 people gathered around the monument. The Chancellor of Oxford University, the Mayor of Oxford, a small group of World War II veterans, and other dignitaries were present. Prayers were read by Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Muslim and Sikh faiths, reflecting the many peoples who served in the World Wars on behalf of Britain. A bagpiper played the haunting “Flower’s of the Forest”, musicians offered “The Last Post” and a solitary bugler gave Reveille. It was a beautifully arranged and moving ceremony in the bright morning sun. Thirty five wreaths were laid around the monument, representing various local units and all branches of the services. And I was pleased to see that, even in the small town of Oxford, a wreath had been thoughtfully sent by the United States ambassador .

This is a long way from the subject of Maryland and 17th-century history. But we are at the point where a major war is now only history, with no one left to relate their experiences about what happened. Early Maryland is the same. We can only come to try and understand it from the documents that survive, a tiny number of buildings, and the broken artifacts from daily life that archaeologists attempt to decipher. In studying that long ago time, we too are engaging in the act of remembering. Colonists to Maryland made many sacrifices. Many never saw their parents or brothers and sisters again. A large number died very young, before being able to experience the opportunity that the colony offered. And the amount of hard, backbreaking work it demanded to build that new society is only now being recognized from studying the skeletons of these Maryland settlers. As in war, creating Maryland also involved casualties, the majority of whom were young men and women in the prime of life. It is just as important for us to remember them, for they helped form the life we have today. I thought of them and the people who have given themselves in later causes when a traditional passage from Laurence Binyon’s For the Fallen was read at this morning’s ceremony:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun, and in the morning,

We will remember them.

At end of this reading, everyone present firmly but softly responded: We will remember them!